Written by: Akshika Jangid

Bollywood movies are often a reflection of society’s triumphs and tribulations with a dramatic turn, but there are some movies that are made not just to entertain but to leave a lasting impact on us — to show the grim reality of real estate development. Jolly LLB 3 is the latest instalment in the courtroom drama franchise, portraying compelling courtroom battles and gripping characters while offering a hard-hitting critique of India’s Land Acquisition Act. The film brings to light the complexities, injustices, and loopholes that plague a law intended to balance development and farmers’ rights. Jolly LLB 3 did attempt to highlight these loopholes but it was somehow lost between the slapstick comedy and emotional drama that it delivered so brilliantly. Well, this article is not about my review of the movie, it goes beyond the courtroom comedy drama and seeks to highlight the central theme of the movie that is the fight for justice when ordinary citizens are crushed by powerful political–business nexuses. Lastly, the emotional turmoil of losing ancestral land combined with bureaucratic apathy and legal challenges plays out on screen with genuine impact.

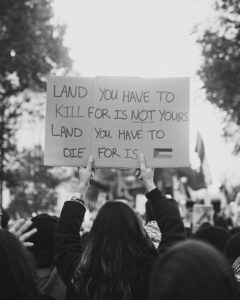

So, when we think of agriculture, our minds often wander to vast fields of crops, bustling markets, and farmers’ livelihoods. In today’s times, our priorities have changed as lately infrastructural development and globalisation has now dominated the discourse. Is this kind of development that uproots the basic livelihood of the marginalized really justified? Today the wealth of a farmer is his land and if we snatch the only piece that gets their earnings without paying heed to proper governance frameworks, then the fault lies with the law not the people.

More Than Just a Legal Drama

Set in Rajasthan’s Bikaner region, Jolly LLB 3 draws inspiration from real incidents like the infamous Bhatta-Parsaul protests of 2011 which shook the nation, where farmers in Uttar Pradesh’s fertile villages resisted land acquisition for the Yamuna Expressway. They were offered compensation vastly lower than the resale price developers charged, resulting in violent clashes and tragic deaths.

Jolly LLB 3 mirrors this injustice in Bikaner, underscoring the disproportionate power dynamics between rural landowners and corporate entities. At its core is the tragic tale of Rajaram Solanki, a poor farmer forced to sell his land to a powerful corporation, only to be left devastated by the inadequate compensation and loss of livelihood—leading to his ultimate sacrifice. Through the eyes of rival lawyers locked in a legal battle, the film exposes how the system meant to protect landowners is riddled with gaps favoring vested interests.

The Land Acquisition Act: Intended Safeguard or Legal Maze?

India’s land acquisition laws have a colonial legacy, dating back to the 1894 Act, which allowed authorities to compulsorily acquire private land for “public purposes”—often without fair compensation or consent. This law was notorious for sidelining farmers and marginalized communities in the name of ‘Development’.

In 2013, the Right to Fair Compensation and Transparency in Land Acquisition, Rehabilitation and Resettlement Act was introduced to address these issues. It mandated fairer compensation, consent requirements, social impact assessments, and rehabilitation provisions. Yet, Jolly LLB 3 subtly attempts to highlight that despite legal reforms, significant loopholes persist in implementation:

- Consent and Coercion: The law requires 70-80% consent from landowners but loopholes allow coercion or manipulation, making consent nominal rather than genuine.

- Compensation Calculation: Compensation is often based on outdated land valuations and excludes income loss, failing to match real market prices developers fetch, leaving farmers shortchanged.

- Rehabilitation and Resettlement: Though mandated, many displaced families never receive adequate rehabilitation or alternate livelihood opportunities, further deepening distress.

- Delays and Litigation: Complex procedures and judicial delays often prolong disputes, draining resources of small farmers while developers wait out legal battles.

Why it Matters

Land acquisition is not just a legal formality but a fraught terrain influenced by socio-political conflicts and flawed policy execution. The film Jolly LLB 3 stokes public discourse, pushing for stronger protections, transparency, and accountability in real estate development—even today—by bringing these issues to the public stage. Pop culture awareness from movies like these makes investors and buyers alert to the deep-rooted ground realities in India’s real estate sector. In the first half of 2025, India saw its highest-ever land transaction volume: about 2,898 acres exchanged hands in 76 major deals, valued at nearly ₹30,885 crore—surpassing all of 2024’s large deals. Tier II and III cities are leading acreage growth, while Mumbai and Bengaluru continue to dominate per-acre value. To foster transparency and reduce disputes, the government is accelerating the digitization of land records—a critical step, but this is only one piece of a much larger puzzle.

Land acquisition in India is far more than a bureaucratic procedure—it intricately entwines complex social realities, political contestations, and historically flawed laws that often disadvantage vulnerable stakeholders. For decades, the 1894 ordinance allowed land to be acquired without proper compensation, meaningful consent from owners, or an avenue of appeal. These deficiencies prompted landmark reforms, notably the 2013 Land Acquisition Bill, which championed fair compensation, transparent processes, and significant community consent—offering rural landowners up to four times higher payouts and banning the acquisition of multi-crop land except for national security.

However, changes introduced through recent ordinances have rolled back many of these safeguards: Section 3(A), for instance, strips away the hard-won provisions for social cause and multi-crop land protection, the requirement for large-scale consent by affected communities, and the guarantee that unused land be returned to farmer within five years. Farmers now risk losing their land—and hope—without fair recourse or compensation, leaving them exposed to indiscriminate corporate development. If the current government attempts to revive the old draconian law threatens to undermine hard-fought progress, replacing meaningful protection with unchecked discretionary powers for private and public projects, and eroding the soul of the 2013 Act, then we will collectively fail as a democratic country.

To end this I remember someone had asked Swami Vivekananda and I quote, ‘what can be worse than losing everything? Swami Vivekanand replied, “that hope by which we can get back everything’.

Way Forward: Reform and Responsibility

The film closes with a call for ongoing reform and vigilance—acknowledging that laws alone cannot solve the systemic neglect of farmers. Fair compensation must be paired with genuine dialogue, rehabilitation, and social equity to ensure that India’s growth does not trample the very communities it depends on.

Jolly LLB 3, through a compelling narrative and courtroom drama, is a timely reminder that the Land Acquisition Act’s loopholes are more than legal technicalities—they are lived realities impacting millions. Beyond the cinematic lens, it urges policymakers, protects farmers, and informs stakeholders about the underlying risks and opportunities as India’s real estate boom transforms cities and rural landscapes alike.