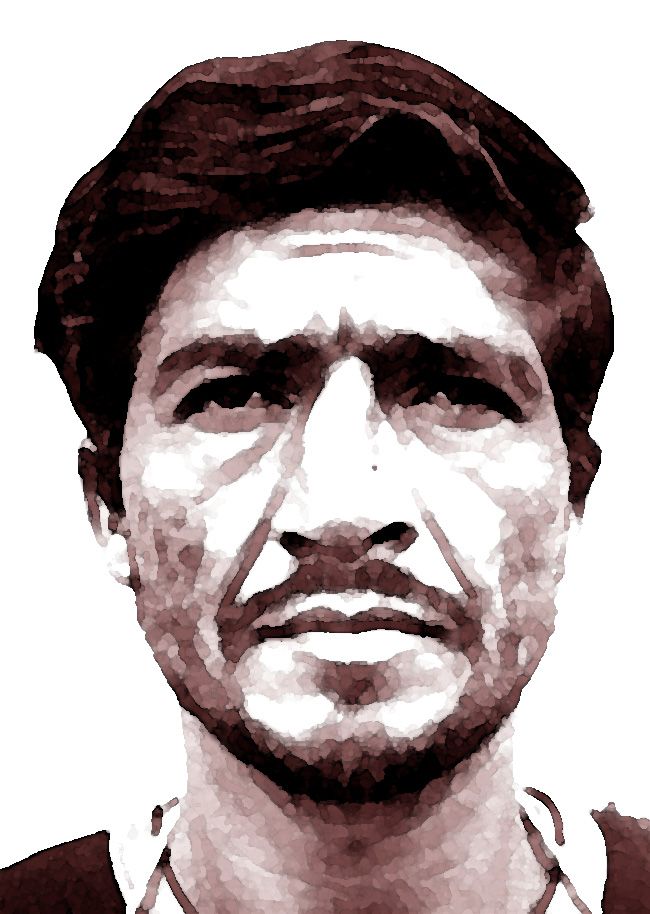

Pedro Alonso López is one of the most horrifying and enigmatic figures in the annals of global criminal history. Nicknamed the “Monster of the Andes,” López’s story is a chilling blend of psychological trauma, unchecked violence, and systemic failure that allowed one of the world’s most prolific killers to vanish into obscurity. His case, frequently cited by criminologists, journalists, and true-crime writers alike, highlights the devastating intersection of poverty, abuse, and law-enforcement gaps across South America.

This long-form article from Riya’s Blogs explores López’s life and the psychological, social, and legal factors that shaped one of the deadliest crime sprees in modern times.

Early Life and Origins

Pedro Alonso López was born on October 8, 1948, in the rural town of Tolima, Colombia, into a life of extreme poverty and violence. His mother, Benilda López de Castillo, was a sex worker raising thirteen children on her own. The young Pedro grew up in an environment marked by neglect, sexual exposure, and street violence.

At age 8, López reportedly witnessed sexual acts daily in his own home and was often beaten for minor disobedience. His early psychological development—already fragile due to deprivation—spiraled when he was sexually assaulted by a teacher after running away from home. This event, by his later admission, “destroyed something” inside him and sparked a deep hatred toward society and women.

By adolescence, López had become a petty criminal, surviving by theft and street scams. At 18, he was caught stealing a car and imprisoned—a punishment that arguably sealed his fate. In prison, he claimed to have been gang-raped repeatedly by other inmates. His revenge was brutal: López murdered three of his attackers, an act that gave him a perverse sense of control.

Psychologists later theorized this experience reinforced his belief that violence was both justifiable and empowering—an essential insight into the psychology of Pedro Alonso López.

Emergence of the “Monster of the Andes”

After his release in the late 1960s, López drifted through Colombia and Ecuador, claiming later that he first began killing young girls around 1969. His victims were typically poor, vulnerable, and often street children—easy prey in countries torn by political instability and economic hardship.

He operated across three nations: Colombia, Ecuador, and Peru, taking advantage of porous borders and minimal inter-country cooperation. His crimes often followed a gruesome pattern: he lured girls—usually between 8 and 12 years old—with promises of gifts or food, then led them to secluded areas where he raped and strangled them.

López’s later confession suggested over 300 murders, an astronomical figure that, if true, makes him one of the most prolific serial killers in recorded history. Authorities in all three countries confirmed at least 110 victims through exhumed bodies—each one a testament to a horrifying level of predation.

Because of the geographical scale and sheer magnitude of his acts, the press dubbed him the “Monster of the Andes.” The name captured both his reach—spanning the spine of South America—and his inhuman cruelty.

Pedro Alonso López’s Victims List

The Pedro Alonso López victims list reads like a tragic demographic of forgotten children: nameless girls from rural villages, indigenous communities, and poor neighborhoods. In Ecuador alone, the police discovered 53 bodies in Ambato after his arrest, many buried in shallow graves. In Colombia and Peru, the total was believed to exceed 250 more.

Most of these victims came from marginalized groups—families who rarely had the means to file missing-person reports. Many disappeared during local market days, where López prowled unnoticed amid crowds.

The Monster of the Andes crimes went undetected for years because of social apathy toward the poor and widespread governmental neglect. Parents’ pleas were often dismissed as “runaway” cases. It was only after patterns emerged—clusters of missing girls in several regions—that the horror began to unfold.

The Confession That Shocked the World

López’s confession remains one of the most chilling in criminal history. Arrested in 1980 after a failed kidnapping attempt in Ecuador, he quickly became the prime suspect behind hundreds of disappearances. When questioned, he shocked investigators by confessing to over 300 murders across South America.

He even led police to gravesites, demonstrating uncanny memory for burial locations. Journalists and criminologists who later reviewed the confession noted his complete lack of remorse—he described his killings as a “mission” to “cleanse” the world of impurity.

Psychologists examining him later characterized López as a psychopath with narcissistic and antisocial traits, coupled with deep-seated sexual sadism. The psychology of Pedro Alonso López remains a case study in how early trauma, neglect, and systemic failure can converge to produce extreme sociopathy.

His own words were haunting:

“I lost my innocence at eight years old. So I decided children should lose theirs too.”

Such statements cemented his image as a cold-blooded predator, not driven by rage or revenge but by a warped moral compass.

Legacy of Fear and Societal Shock

The magnitude of López’s crimes not only terrorized families but also shook the perception of safety across the Andean nations. For the first time, international organizations and Interpol were drawn into a case involving a South American serial killer whose operations transcended borders.

At the time, serial killings were often viewed as a phenomenon of industrialized nations. López forced criminologists to confront the fact that such horrors were not confined to the West. The case opened discussions on the South American serial killers phenomenon, influencing future policing and psychological profiling in the region.

The Arrest and Capture of Pedro Alonso López

By 1980, panic had gripped Ecuador. Dozens of young girls had gone missing from Ambato and nearby provinces, leaving entire communities haunted by fear. Parents began forming search groups, and local newspapers published pleas for help. Despite increasing pressure, police struggled to identify a pattern — until one fateful morning in March 1980, when their luck changed.

Pedro Alonso López was caught in the act of attempting to abduct a 9-year-old girl from a market in Ambato. The child’s mother, suspicious of the stranger’s behavior, intervened and alerted the authorities. When police detained López, they discovered trinkets, children’s jewelry, and small dolls in his bag — items later identified as belonging to missing victims.

Initially, López appeared calm and dismissive. But under interrogation — and faced with mounting physical evidence — his demeanor shifted from denial to a horrifying openness. He began speaking with pride about his “work,” calling himself a “missionary of death.” It was during this interrogation that he admitted to killing more than 300 girls across Colombia, Ecuador, and Peru.

The Startling Confession

The Pedro Alonso López confession is among the most chilling ever recorded. He did not plead insanity or deny his actions; instead, he claimed he was “doing God’s will.”

When Ecuadorian police initially dismissed his claims as exaggerations, López proposed a grim demonstration. He led investigators to dozens of burial sites in remote rural areas, where bodies of missing girls were found exactly where he described. In total, over 50 graves were uncovered in Ecuador alone, confirming the terrifying scale of his crimes.

López even claimed that when heavy floods destroyed some of his burial sites, he “felt sadness” because he “lost his little girls.” He told investigators:

“I like the girls because they are pure, beautiful, and innocent. I never hurt the ugly ones.”

These words cemented his identity in the media as “The Monster of the Andes” — a man devoid of empathy, whose monstrous actions defied comprehension.

Trial and Sentencing in Ecuador

The Pedro Alonso López trial in Ecuador began later in 1980 and immediately drew international attention. Ecuador’s justice system was unprepared for such a case. There was no legal precedent for a killer of his scale.

Despite confessing to 300+ murders, he was formally convicted of 110 murders — the number that could be verified through physical evidence. The judge declared him guilty, but Ecuador’s penal code at the time set the maximum sentence at 16 years, even for mass murder.

Thus, one of the deadliest serial killers in world history was sentenced to just 16 years in prison — an outcome that horrified both Ecuadorians and the international community.

Journalists from across the globe flocked to cover the story, stunned that a man who admitted to murdering hundreds of children could receive such a short punishment. The Ecuadorian government defended the decision by citing constitutional limits and the absence of a life-sentence or death penalty statute.

López’s Prison Life: Manipulation and Comfort

While incarcerated, López continued to manipulate those around him. He displayed a strange duality — at times quiet and polite, at others eerily boastful. Guards described him as “intelligent but completely cold.”

Psychologists studying him noted that López lacked remorse and exhibited classic psychopathic traits — charm, deceit, and a total absence of guilt. The psychology of Pedro Alonso López fascinated criminal profilers because he was not motivated by greed or revenge, but by compulsion and a belief that his killings were righteous.

He often boasted that “the authorities are too stupid” to stop him, and that once released, he would “continue where he left off.” These statements were largely dismissed as delusional bravado — a tragic misjudgment that would soon haunt investigators.

Despite the scale of his crimes, López reportedly lived a relatively comfortable prison life. He gained notoriety among inmates, some of whom feared him, while others treated him like a dark celebrity.

The Shocking Release

In 1994, after serving 14 years of his 16-year sentence (with two years reduced for good behavior), Pedro Alonso López was released from prison. The decision caused public outrage in Ecuador and beyond. The media branded the justice system “a failure,” while victims’ families protested, fearing that López would kill again.

However, Ecuadorian authorities claimed they had no legal basis to hold him longer. López was handed over to Colombian authorities, as he was a Colombian citizen, and briefly imprisoned for a previous murder in his home country.

After only a few years, in 1998, López was declared “mentally rehabilitated” by a Colombian psychiatrist and released once more — a move that remains one of the most controversial in global criminal history.

Pedro Alonso López’s Capture and Release: The Aftermath

Following his release, López disappeared entirely. Interpol issued alerts, and Colombian police kept minimal surveillance, but he soon vanished. Some reports claim he was briefly rearrested in 2002 after being suspected of another girl’s disappearance, though no official record was ever confirmed.

Since then, his whereabouts have remained unknown, and authorities have feared that he may have resumed his killing spree or died anonymously in Colombia’s rural slums. As of today, the Pedro Alonso López missing whereabouts continue to intrigue criminologists and terrify the public alike.

If still alive, he would be in his late seventies — free, unrepentant, and possibly still capable of manipulation. His release stands as a haunting reminder of what happens when justice systems lack mechanisms to handle psychopathic repeat offenders.

Public Reaction and Global Outrage

López’s release ignited international outrage and debate over how nations should handle serial killers, especially in countries with limited forensic or psychiatric infrastructure. The case led to renewed efforts to strengthen South American criminal justice laws, particularly regarding serial offenses, maximum sentencing, and cross-border investigations.

The story of Pedro Alonso López — the Monster of the Andes — became a cautionary tale. It revealed the vulnerability of impoverished societies, the indifference toward missing children, and the catastrophic consequences of treating extraordinary crimes with ordinary laws.

Inside the Mind of the Monster: The Psychology of Pedro Alonso López

The crimes of Pedro Alonso López are not only a tragic reflection of social neglect but also a complex psychological study. To understand the “Monster of the Andes,” one must confront the disturbing intersection of trauma, narcissism, sexual pathology, and moral void that defined his psyche.

When criminologists examined López, they found him to be lucid, articulate, and eerily calm — a man who could recount the murder of hundreds of children with clinical detachment. Unlike impulsive killers, López was methodical, patient, and ritualistic. His intellect and composure made him more terrifying than any frenzied murderer.

Childhood Trauma and the Birth of Violence

The psychology of Pedro Alonso López is deeply rooted in his early trauma. Born into poverty, abandoned by his father (who was reportedly killed during Colombia’s civil conflict), and raised by a mother who exposed him to prostitution, López grew up without affection or stability.

At age 8, he was sexually assaulted — an experience that shattered his already fragile emotional world. Later, during interviews, López described that moment as a turning point:

“Something inside me died that day.”

From that moment on, he began to view innocence not as something to protect, but as something to destroy — a perverse reversal of his victimhood. His attacks on young girls were not random acts of rage but rather repeated symbolic recreations of his own lost innocence.

In psychological terms, López developed displaced aggression — inflicting upon others the suffering once imposed upon him. Yet what made him exceptionally dangerous was his complete emotional disconnection from the act.

Psychopathy and Sadism

López displayed classic signs of psychopathy, a condition marked by lack of empathy, manipulative charm, and moral insensitivity. According to forensic psychiatrists who examined him in Ecuador, he was “an intelligent man incapable of guilt.”

He would often describe his victims not as humans, but as “dolls” or “toys.” He derived not just sexual pleasure from control, but psychological gratification from domination. His killings were not impulsive — they followed a precise pattern. He would stalk small rural markets, isolate a child, offer trinkets, and lure them to a secluded spot. Once alone, he reportedly strangled them while gazing into their eyes, claiming he wanted to “watch their soul leave.”

This calm, ritualistic control indicated sexual sadism, a paraphilia in which pleasure is derived from others’ suffering. Criminologists later compared López to killers like Ted Bundy and Andrei Chikatilo, though López’s targeting of prepubescent victims made his pathology even darker.

Victimology: Why Children?

The Pedro Alonso López victims list reveals an unsettling consistency — nearly all victims were girls aged between 8 and 12, most from impoverished or indigenous communities in Colombia, Ecuador, and Peru.

He specifically chose children because, in his words, “they were easier to trust and had the purest souls.” He believed killing them released him from his own “inner demons.”

For investigators, his reasoning was both absurd and terrifying. His selection of victims reflected a predatory understanding of social invisibility: poor children were least likely to be searched for, their disappearances dismissed by overburdened police.

This insight is part of why the Monster of the Andes crimes went undetected for so long — López understood that the system would not care about his victims.

Ritual and Compulsion

Every killer leaves behind a pattern — and López’s was disturbingly systematic. He often claimed to feel “a dark hunger” that grew every few days until he killed again. His crimes were driven by compulsion, not necessity.

He once told a journalist:

“After the first time, I could not stop. It was like a need. I was born to do this.”

In psychological analysis, this aligns with compulsive homicidal behavior, similar to obsessive disorders but with violent outlets. López killed to silence the urge, but each act only intensified it.

Unlike impulsive murderers, López planned his killings meticulously. He would travel between countries, change disguises, and use transient routes to avoid detection. Authorities believe he may have exploited chaotic political conditions — the guerrilla conflicts and border instability of the 1970s — to move freely across regions.

Perceived Morality and Grandiosity

One of the most disturbing aspects of López’s psyche was his twisted moral logic. He saw his crimes as divine work, claiming he was “chosen” to punish immorality. This delusional self-justification mirrors the “God complex” often observed in narcissistic psychopaths.

He genuinely believed that killing young girls preserved their innocence — an echo of his warped childhood trauma. In this way, López’s acts were not random but ritualistic, built around an ideology of purification.

This form of moral displacement is what allowed him to appear calm and rational even while discussing atrocities. He did not see himself as a monster, but as a misunderstood instrument of justice — a theme that makes his psychological profile particularly disturbing.

Expert Assessments and Debates

During and after his incarceration, multiple psychiatrists evaluated López. The conclusions were unanimous: he was criminally sane but morally absent. That meant he understood right from wrong but simply did not care.

This placed him squarely in the realm of psychopathic serial offenders rather than psychotic ones. He was not hallucinating, delusional, or insane — he was coldly calculating, aware of his crimes, and devoid of remorse.

Dr. Ramón Lasso, one of the Ecuadorian psychiatrists who examined him, remarked:

“He speaks of murder the way one speaks of washing dishes. There is no tremor in his voice, no darkness in his eyes — only vacancy.”

The Broader Impact on Criminology

The case of Pedro Alonso López — the Monster of the Andes — became a benchmark in Latin American criminology. It forced psychologists and law enforcement agencies to re-evaluate their understanding of serial killers in developing nations.

Until López, many believed serial homicide was a largely Western phenomenon. His case shattered that myth, revealing that under conditions of poverty, neglect, and social chaos, psychopathic behavior could emerge anywhere.

He became the subject of multiple criminology studies, and his profile is still taught in forensic psychology programs worldwide.

Unrepentant to the End

Even after years in prison, López never expressed remorse. He maintained that his victims “wanted to die” and once chillingly claimed he was “doing them a favor.” When asked if he regretted his actions, he replied:

“Why should I? They are in heaven. I am here, where I belong.”

This level of moral disassociation is what makes López’s psychology one of the most extreme examples of human depravity ever recorded.

Aftermath and Disappearance: The Vanishing of a Monster

When Pedro Alonso López walked free in 1998, the world was left stunned. His release was not merely a legal technicality — it was a global failure of justice. A man who confessed to killing over 300 girls was declared “rehabilitated” and allowed to vanish into one of the most lawless regions on Earth.

Shortly after his release, López was reportedly handed a small amount of money and identification documents by Colombian authorities. Within days, he disappeared without a trace. Authorities later admitted they did not monitor him, citing lack of resources and jurisdictional confusion.

The Interpol notice issued in 2002 listed López as wanted for questioning after the disappearance of another young girl near Tunja, Colombia. Local rumors claimed he had returned to his old habits, luring and murdering again. However, no body was ever found, and no official arrest followed.

From that point on, the whereabouts of Pedro Alonso López became one of the great mysteries of modern crime. Some claim he was killed by vigilantes in rural Colombia; others believe he fled deeper into the Andes or crossed into Venezuela under a false name. A few criminologists even suggest he may have died naturally, buried anonymously in a pauper’s grave — a quiet end to a life that thrived on horror.

Regardless of the truth, one fact remains: no one knows where the Monster of the Andes is.

International Reaction and Legal Lessons

López’s release in 1998 reignited global debate about justice systems in developing nations. How could a man who confessed to murdering hundreds of children serve only 14 years in prison? How could he be released without monitoring, psychiatric treatment, or rehabilitation programs?

The Ecuadorian government defended its actions, insisting that the country’s penal laws at the time capped all sentences at 16 years — even for serial murder. Colombia, facing its own civil unrest and underdeveloped legal infrastructure, was equally ill-equipped to contain him.

As international outrage spread, Interpol issued alerts to member nations, urging vigilance. However, the lack of cross-border criminal databases and modern DNA systems in the 1990s meant López effectively disappeared into anonymity.

The Pedro Alonso López capture and release saga thus became a textbook example of systemic collapse — a failure not only of law enforcement but of international cooperation. It demonstrated how killers could exploit bureaucratic weakness, especially across regions fractured by poverty and corruption.

In criminology circles, López’s name became synonymous with “the loophole killer” — a man who escaped accountability not because of cunning but because of legal inadequacy.

The Monster of the Andes in Cultural Memory

Over the decades, Pedro Alonso López — the Monster of the Andes — has transcended criminal infamy to become a symbol of unchecked evil. His story has inspired countless documentaries, case studies, and books exploring the psychology of serial killers and the fragility of justice in developing nations.

In the early 2000s, several investigative journalists retraced his path across Colombia, Ecuador, and Peru, documenting interviews with families of victims and retired police officers. Their stories formed the basis for books and true crime studies such as The Monster of the Andes (by Ron Laytner, who also interviewed López in prison) and multiple televised features that revisited his crimes.

In these documentaries, López appears calm, smiling, and disturbingly articulate — explaining his motives as though recounting routine memories. This footage shocked audiences, making him one of the most haunting faces in true crime media.

His case also influenced academic research into South American serial killers, a field once overshadowed by Western studies. It highlighted how cultural, economic, and social instability can incubate violent psychopathy in any part of the world.

Impact on South American Society

The aftermath of López’s crimes profoundly affected the Andean nations. Ecuador, Colombia, and Peru all introduced stricter laws for violent crimes in the years that followed. Maximum prison terms were extended, psychological evaluations became mandatory for violent offenders, and cross-border policing initiatives began under Interpol’s coordination.

Forensic teams were established to better identify missing children, and NGOs began advocating for stronger protections for rural and indigenous youth — the very demographic López targeted.

Yet, the scars remain. In many Andean towns, López’s name is still whispered among parents as a warning — a reminder of how society failed its most vulnerable.

The Psychology of Evil: How López Redefined Serial Crime

In criminological literature, the psychology of Pedro Alonso López continues to be cited as one of the clearest examples of organized psychopathy combined with sexual sadism.

He did not act out of compulsion alone; his killings were driven by a philosophy of control — a belief that he was restoring balance to a corrupt world.

Experts studying his mind draw parallels between López and figures like Ted Bundy, Gary Ridgway, and Andrei Chikatilo, yet his case stands apart for two reasons:

- Scale: He confessed to over 300 murders — more than nearly any serial killer in history.

- Escape: He remains the only such killer ever released and then lost from all global surveillance.

This combination of enormity and enigma has turned López into a dark legend, studied not only for what he did but for what he represents — the terrifying possibility that evil can hide in plain sight, protected by indifference.

Is Pedro Alonso López Still Alive?

Perhaps the most haunting question remains: Is Pedro Alonso López still alive?

If born in 1948, he would be around 77 years old today (as of 2025). Some reports claim that in 2002 he was briefly arrested in Colombia under suspicion of another child’s murder but released again for lack of evidence. Others believe he died during internal conflicts in rural Colombia, where guerrilla groups often executed outsiders.

Interpol still classifies his whereabouts as unknown, and no body matching his identity has ever been found. Whether dead or alive, his shadow lingers across the Andes — a ghostly symbol of how fear, law, and morality can fail together.

Why Pedro Alonso López Still Terrifies the World

There are many prolific serial killers in history — Gary Ridgway, Ted Bundy, Luis Garavito — but few evoke the same dread as Pedro Alonso López, the Monster of the Andes. His crimes stretch across three nations, his victims exceed hundreds, and his final disappearance erases closure.

He embodies three of humanity’s deepest fears:

- That evil can be ordinary and rational.

- That justice can be powerless.

- That monsters sometimes simply walk away.

The López case continues to be referenced in criminology, ethics, and sociology courses. It’s a case that asks uncomfortable questions about the nature of rehabilitation, moral insanity, and international justice.

Even decades later, his story reminds us that the absence of accountability is itself a crime — one that society committed against its own children.

FAQs: Pedro Alonso López — The Monster of the Andes

Who was Pedro Alonso López?

Pedro Alonso López was a Colombian serial killer known as the “Monster of the Andes,” who confessed to murdering more than 300 young girls across Colombia, Ecuador, and Peru between 1969 and 1980.

Why was he called the “Monster of the Andes”?

He earned the name due to the massive scale of his crimes, which spanned the Andean mountain regions of South America and involved an unimaginable number of victims.

How many victims did López claim to have killed?

He confessed to over 300 murders, though only 110 were officially confirmed through recovered bodies.

How was Pedro Alonso López caught?

He was caught in 1980 in Ambato, Ecuador, while attempting to abduct a young girl. His arrest led to his confession and the discovery of dozens of graves.

What happened during his 1980 trial in Ecuador?

López was convicted of 110 murders and sentenced to 16 years in prison, the maximum penalty allowed by Ecuadorian law at the time.

Was López ever released from prison?

Yes. In 1994, after serving 14 years, he was released and later transferred to Colombia, where he was briefly detained before being declared rehabilitated in 1998.

Where is Pedro Alonso López now?

His whereabouts are unknown. Some believe he was killed by vigilantes; others suspect he may have continued killing in remote regions.

Why is his case one of the most shocking in history?

Because of the scale of his crimes, the leniency of his sentence, and his disappearance after release — making him one of the most prolific and elusive serial killers ever recorded.

Are there books or documentaries about López?

Yes. Multiple documentaries and investigative reports, including interviews conducted by journalist Ron Laytner, explore López’s story in detail. His case also appears in many criminology and true-crime compilations.

Conclusion: The Enduring Shadow of Pedro Alonso López

Decades after his disappearance, Pedro Alonso López — the Monster of the Andes — remains a haunting testament to the limits of justice and the depths of human depravity. His name still echoes through Andean towns and criminal psychology classrooms alike — a reminder that evil, when uncontained, doesn’t vanish; it evolves in silence.

Through the lens of this case, societies are forced to confront a terrifying truth: the real monsters are not those in stories, but those we fail to stop.

And so, the world waits — not for his return, but for the answers that never came.

Want to read a bit more? Find some more of my writings here-

Book Review: Harry Potter and the Goblet of Fire

The Name I Never Got to Say: A Miscarriage Poem for the Baby I Dreamed Of

The Victorian Era: A Tapestry of Elegance, Innovation, and Transformation

I hope you liked the content.

To share your views, you can simply send me an email.

Thank you for being keen readers to a small-time writer.