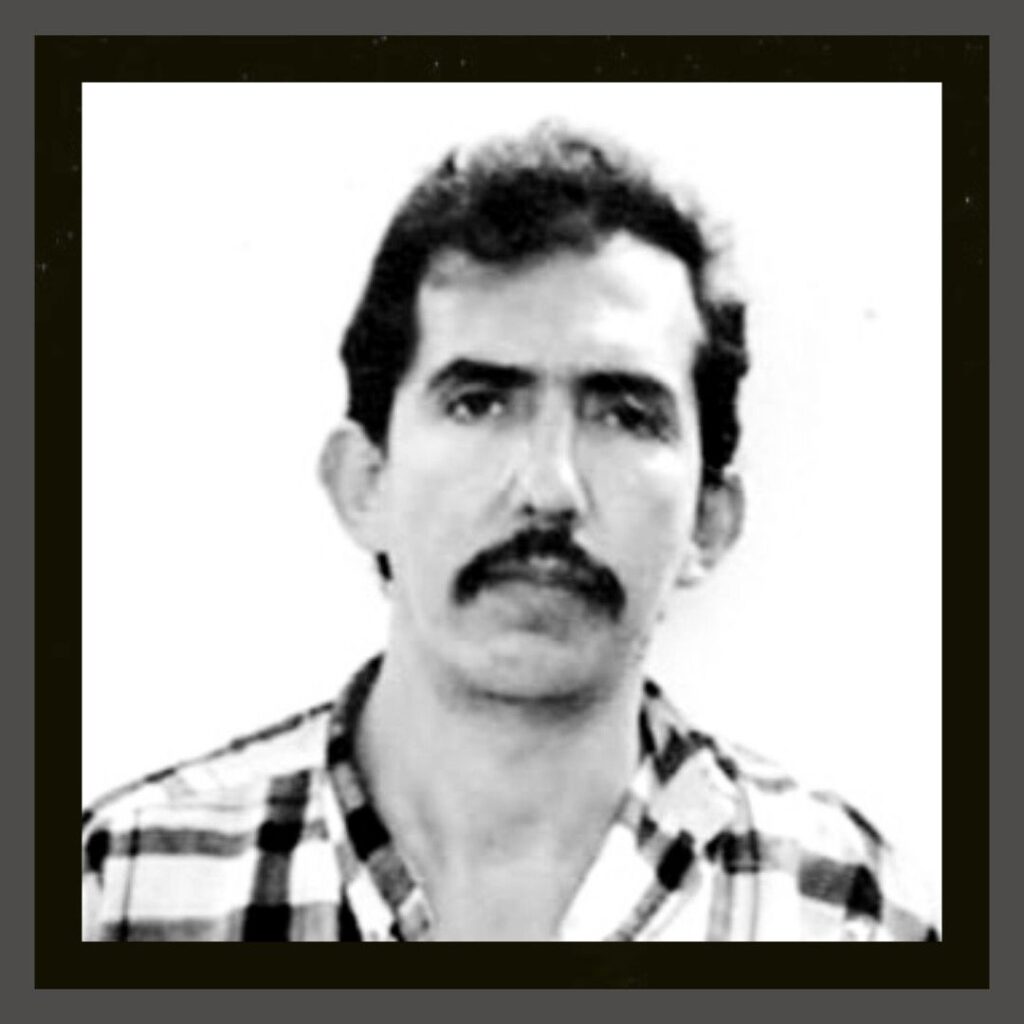

When you think about the darkest corners of humanity, one name stands chillingly above the rest — Luis Alfredo Garavito Cubillos, infamously known as “La Bestia” (The Beast). To this day, Garavito is considered one of the world’s most prolific serial killers, responsible for the brutal deaths of at least 138 young boys across Colombia, and possibly hundreds more throughout South America.

His story is not just one of unspeakable horror, but also of a society’s struggle to understand how such evil could exist — and how a man like Garavito managed to evade justice for nearly a decade.

This article by Riya’s Blogs dives deep into the life, crimes, psychology, and ultimate fate of Luis Garavito, exploring the terrifying details behind the man who became a symbol of Colombia’s most haunting chapter.

Early Life: The Making of a Monster

Luis Garavito was born on January 25, 1957, in Génova, Quindío, Colombia, into a large and deeply troubled family. From his earliest years, he endured severe abuse — both physical and psychological — that would leave scars too deep to heal. His father was a violent alcoholic who routinely beat his wife and children, while his mother, powerless and submissive, often ignored his suffering.

In later interviews, Garavito recounted that his father forced him to witness domestic violence, punished him harshly for minor mistakes, and mocked him in front of others. This emotional torment would form the psychological foundation for the rage, shame, and perversion that defined his later life.

As a child, Garavito displayed many classic behavioral red flags associated with future violent offenders — cruelty toward animals, obsessive lying, and outbursts of uncontrolled anger. He struggled in school and often fought with classmates, but was described by teachers as polite and articulate when he wanted to appear “normal.”

Behind this facade, however, lurked deep insecurity and repressed trauma. He later admitted to being sexually abused by a neighbor when he was around eight years old — a devastating experience that, according to criminologists, may have contributed to his later compulsion to reenact domination and control through violence.

A Life of Deception and Drift

By his teenage years, Garavito had become adept at manipulating others. He dropped out of school and drifted from job to job, working as a salesman, store clerk, and occasionally as a charity collector. He was charming enough to gain people’s trust but unreliable, often moving from one Colombian town to another whenever suspicions arose about his behavior.

During the 1980s and 1990s, Colombia was in chaos — with civil unrest, guerrilla warfare, and economic instability dominating daily life. Thousands of displaced children roamed the streets, homeless and vulnerable. This tragic social backdrop provided Garavito the perfect hunting ground. His victims — mostly boys aged 6 to 16 — were among the poorest and most defenseless members of society, often living without families or government protection.

Using various disguises, Garavito lured children by posing as a teacher, priest, or social worker, promising food, money, or education. Once he gained their trust, he led them to isolated rural areas, where he carried out acts of extreme sexual violence and torture before killing them — usually by strangulation.

Each crime bore the same chilling pattern, a ritual of dominance that suggested an inner compulsion beyond rational explanation.

The Beginning of a Killing Spree

Between 1992 and 1999, Garavito’s reign of terror unfolded across Colombia like a silent plague. He traveled from town to town, leaving behind a trail of missing children whose disappearances were often dismissed as runaways or casualties of war. Because of Colombia’s fragile law enforcement infrastructure, no one initially connected the dots — the crimes spanned multiple provinces and went unnoticed in the chaos of the 1990s.

As the number of missing boys rose dramatically, local villagers began discovering mass graves and skeletal remains, often with evidence of horrific mutilation. Forensic experts identified consistent patterns — ropes, alcohol bottles, razor blades, and children’s clothing left near the sites. It was clear these were not isolated murders, but the work of a methodical serial killer.

The Colombian media soon caught wind of the mystery and began calling the unknown murderer “El Monstruo de Génova” — The Monster of Génova — after Garavito’s birthplace. But the nickname that stuck, “La Bestia,” perfectly captured the collective horror his crimes inspired.

A Psychological Abyss

Criminal psychologists who later studied Garavito’s confessions and behavioral records described him as a textbook case of antisocial personality disorder with deep-seated sadistic sexual tendencies. Unlike many serial killers who target adults, Garavito’s fixation on prepubescent boys stemmed from a desire to control and inflict pain — acts through which he reenacted his own early abuse.

He admitted to feeling “possessed by a demon” during his crimes and often claimed afterward that he was overcome with remorse. Yet his remorse was shallow — he described his victims’ agony in shocking detail during his confession, without genuine empathy.

In fact, investigators noted that Garavito kept detailed mental records of his killings — the dates, locations, and number of victims — as if cataloging trophies in his mind.

The Capture of Luis Garavito: Unmasking “La Bestia”

By the late 1990s, Colombia had grown used to violence — but the scale and pattern of the child murders began to alarm even the most desensitized citizens. In rural departments such as Risaralda, Valle del Cauca, and Quindío, villagers repeatedly found shallow graves filled with the skeletal remains of young boys, their hands tied, their clothes torn, and their skulls marked with blows.

Police initially believed the crimes were the work of satanic cults or paramilitary groups, given the brutality and ritual-like patterns. Yet a few detectives began to notice something chilling: the crime scenes all featured empty liquor bottles, torn pornographic magazines, and ropes of the same type. Someone meticulous — and mobile — was responsible.

In 1997, an investigator in Pereira, a city in western Colombia, began connecting the dots between several missing-child cases. He noticed that witnesses in multiple towns described a thin, middle-aged man wearing glasses who offered candy or money to boys. One child who narrowly escaped his grasp described him as friendly at first but “different when we were alone.”

The turning point came in 1999, when the body of a boy named Jair was found near Pereira. Inside the field where the body lay, police found discarded receipts, a notebook, and a pair of broken glasses — items that would lead them straight to Luis Alfredo Garavito.

Arrest and Interrogation

Garavito was arrested later that year while attempting to assault another child. He had changed his appearance — shaved his mustache, grown his hair — and carried a fake ID under the name “Bonifacio Morera Liscano.” At first, he denied any wrongdoing, but police soon discovered photographs, child clothing, and notes that tied him to the multiple murder scenes.

When questioned, Garavito seemed oddly composed. He spoke softly, claiming he was being “persecuted by the devil.” Over the following days, however, investigators began presenting the mountain of forensic evidence against him — DNA traces, blood patterns, witness statements, and the telltale glasses. Eventually, Garavito broke.

What followed was one of the most disturbing confessions in criminal history.

Garavito admitted to raping, torturing, and murdering more than 140 boys between 1992 and 1999, many of them street children or orphans. In his own words, he said, “I lost control. I could not stop myself. It was as if another person lived inside me.”

He described his methods with unnerving precision — luring boys with promises of money or food, walking them to isolated hillsides, sexually abusing them, and strangling them as they begged for mercy. He drew maps of the burial sites and gave police details of victims never before reported missing.

The Confession and Public Outrage

When Garavito’s confession became public, Colombia erupted in outrage. The media dubbed him “El Monstruo de Colombia”, and his face appeared on every front page. Parents wept on live television, desperate to know if their missing sons were among his victims.

Investigators exhumed over 100 bodies from multiple locations across Colombia based on Garavito’s directions. The patterns were unmistakable — every victim was a boy between 6 and 16, each assaulted, tortured, and strangled.

In an attempt to secure leniency, Garavito cooperated fully, leading police to gravesites and explaining his psychological impulses. Yet no amount of cooperation could temper public fury. He confessed with such detachment that even seasoned detectives wept in the interrogation rooms.

One investigator later recalled:

“He remembered the number of buttons on their shirts, the color of their shoes. But when we asked him about their names, he could not recall one. That’s when we knew — he didn’t see them as children. He saw them as prey.”

Trial and Sentencing: Justice within the Law’s Limits

In 2000, Luis Garavito stood trial for the murders of 138 confirmed victims, though the true number could be higher than 300. Colombian prosecutors charged him with multiple counts of murder, kidnapping, and sexual assault, making it one of the largest criminal cases in South American history.

Yet the country’s legal system presented a moral paradox. Colombia had abolished the death penalty decades earlier, and its maximum prison sentence — even for the most heinous crimes — was 40 years at that time (later adjusted to 60).

Despite the unimaginable scope of his crimes, Garavito could not be sentenced to death or life imprisonment. Instead, his total combined convictions reached an astonishing 1,853 years and 9 days — the longest nominal sentence in Colombian history. However, due to legal limits, his effective sentence was capped at the national maximum.

This sparked enormous debate both inside and outside Colombia. For many, the idea that the world’s most prolific child killer could one day walk free was unthinkable. The families of victims organized protests, demanding changes to Colombian sentencing laws.

During his trial, Garavito appeared remorseful, often crying as he addressed the court — but psychologists later described his tears as performative, the behavior of a narcissist seeking pity rather than redemption.

Inside Prison: The Beast Caged

Garavito was incarcerated in a maximum-security prison in Valle del Cauca, where he was kept under heavy protection. Other inmates, outraged by his crimes, reportedly tried to kill him several times. For his safety, he was isolated and moved between cells to prevent coordinated attacks.

In interviews conducted by criminologists and journalists, Garavito presented himself as a man who had “found God” and was “helping other prisoners reform.” He claimed to have accepted Jesus Christ and spent his days reading the Bible and writing notes about morality. Yet few believed in his transformation.

Investigators and psychologists maintained that his psychopathy was so deep that true rehabilitation was nearly impossible. He continued to show a lack of genuine empathy, often referring to his crimes in the past tense as if they were a separate part of him — a defense mechanism typical of serial offenders seeking detachment from guilt.

During his imprisonment, he also cooperated with several criminological studies aimed at understanding serial killers’ mental patterns. Experts who interviewed him described him as articulate and even charming at times — the same charisma he used to lure victims. But beneath that charm remained the calculating predator who once terrorized an entire nation.

Legal Controversies: Could He Ever Be Released?

As years passed, Colombia’s justice system continued to review Garavito’s sentence under evolving penal laws. Since Colombian law allowed sentence reductions for good behavior and cooperation, rumors began circulating in the 2010s that he could qualify for early release.

The news triggered widespread outrage. Editorials, public petitions, and political debates dominated national headlines. Human-rights groups argued that releasing Garavito would mock the suffering of victims and undermine trust in the justice system.

Government officials later clarified that, while technically eligible for review, Garavito would never be released because of his high risk of reoffending and the severity of his crimes. The Colombian Attorney General’s Office publicly opposed any reduction, ensuring he would remain behind bars for the rest of his life.

Still, the legal loophole exposed a profound issue in Colombian criminal justice — how to reconcile constitutional human rights with the need for justice in cases of unparalleled cruelty.

A Symbol of Evil

By the early 2020s, Luis Garavito had become less a man than a symbol — a cautionary tale of systemic failure, unchecked trauma, and the thin line between civilization and savagery. True-crime documentaries and university studies worldwide began examining his psychology as an example of organized sexual sadism and pathological compulsion.

Colombians continued to live with the memory of La Bestia. His name, once whispered in fear, became shorthand for every parent’s worst nightmare.

The Psychology of “La Bestia”: Inside the Mind of Luis Garavito

To understand Luis Garavito is to step into one of the darkest psychological labyrinths ever recorded. Unlike impulsive murderers driven by rage or revenge, Garavito was a calculating predator — intelligent, manipulative, and deliberate in every step. Criminologists have long classified him among the organized serial killers, those who plan meticulously, charm their victims, and leave behind almost no evidence.

What made him particularly horrifying was the combination of intelligence and deviance. He was neither insane nor delusional in the traditional psychiatric sense. Instead, he exhibited the classic markers of psychopathy — a lack of empathy, superficial charm, manipulativeness, and complete disregard for others’ suffering.

When interviewed in prison, Garavito often spoke of his crimes as though they had been committed by “another man.” He claimed to have been possessed by uncontrollable urges, describing his victims as “temptations sent by the devil.” But experts who analyzed his taped confessions noted that these statements were self-serving narratives, carefully constructed to reduce responsibility and gain sympathy.

Psychologist Dr. Silvia Restrepo, one of the professionals involved in the Garavito interviews, described him as “emotionally empty but cognitively sharp.” She noted that he used religious phrases to mask his guilt, but beneath his words was a consistent undertone of self-pity rather than remorse.

A Profile of Sadism and Control

Garavito’s crimes were not spontaneous acts of violence; they were the result of ritualized sadism. Each killing followed a near-identical sequence: the lure, the isolation, the torture, and the killing — all of which gave him psychological gratification.

In his own statements, Garavito admitted that his victims’ cries of pain and fear made him feel “powerful,” and afterward, he would often drink heavily to “forget.” This cyclical pattern — control, violence, guilt, and temporary remorse — mirrors the behavioral blueprint of compulsive serial predators studied in criminology.

Investigators found that Garavito carried a notebook filled with personal notes and sketches, documenting the locations of killings, dates, and even reflections on his impulses. It wasn’t just murder — it was ritual, a compulsive need to dominate and destroy the innocence he himself lost as a child.

Some experts have compared his psychological makeup to that of Pedro López (another Colombian serial killer known as “The Monster of the Andes”) — both men emerging from childhood abuse and social neglect, and both channeling that trauma into acts of unspeakable violence.

However, unlike López, Garavito’s focus on children and the sheer number of victims made him a unique study in mass predation, one that forced Colombia to confront the failure of its social safety nets.

Religious Conversion and the Facade of Redemption

During his imprisonment, Luis Garavito claimed to have undergone a spiritual transformation. He told interviewers he had found God and sought forgiveness for his crimes. He began reading the Bible daily, offering spiritual advice to other inmates, and even participated in moral rehabilitation programs organized by the prison.

But few believed him.

Prison guards and psychologists reported that Garavito’s “conversion” often seemed strategic, coinciding with moments when he hoped for sentence reductions. His demeanor changed dramatically depending on who he was speaking to — gentle and remorseful with clergy, analytical and emotionless with doctors.

A former warden once commented:

“Garavito could recite scripture as if he were a priest, but the moment you asked him about a child, his eyes went cold. There was no humanity there — only calculation.”

His case became central to Colombia’s debate on rehabilitation versus punishment. Could someone like Luis Garavito — who had destroyed the lives of hundreds of families — ever truly be reformed? Most experts agreed the answer was no. His crimes were driven by deep-rooted psychosexual disorders, impossible to cure, only contain.

The Release Controversy: A Nation in Panic

The Luis Garavito release controversy began around 2015, when media outlets reported that, under Colombia’s penal code, Garavito might become eligible for parole or early release after serving part of his sentence for good behavior and cooperation.

The news spread like wildfire. Parents, activists, and lawmakers flooded television debates and social media, demanding that the government ensure he remained imprisoned for life. Protesters held signs reading “Nunca más — Never again” outside the Ministry of Justice, symbolizing the collective trauma of a nation that had suffered too much violence.

International media, including the BBC and Reuters, picked up the story, calling Garavito’s case a legal and moral test for Colombia. While the law technically allowed for review, Colombian officials quickly clarified that Garavito would never walk free, citing both the magnitude of his crimes and ongoing psychological evaluations labeling him a “permanent threat to society.”

This controversy sparked deeper questions about the limits of justice in a constitutional democracy. Should human rights protections apply equally to all — even to those who showed none to others? Colombia’s constitution forbade life imprisonment and the death penalty, leaving legal scholars divided between the principles of humanity and the need for irreversible punishment.

Ultimately, the government amended several sentencing guidelines, ensuring that serial killers and sexual predators could face up to 60 years in prison, effectively closing the loophole that once made Garavito’s release even theoretically possible.

Final Years and Death in Prison

In his later years, Luis Garavito’s health deteriorated sharply. Years of confinement, a sedentary lifestyle, and growing public hatred took their toll. He developed leukemia and suffered from other chronic illnesses, leading to frequent hospitalizations under guard.

By this time, he was no longer the cunning, composed man who once eluded capture — he was frail, visibly aged, and largely forgotten by the world. When asked in a 2018 interview whether he regretted his crimes, Garavito gave a chillingly hollow response:

“Yes, I ask forgiveness from God and the families. But only He can judge me now.”

On October 12, 2023, Colombian prison authorities confirmed that Luis Alfredo Garavito Cubillos had died of natural causes in a hospital in Valledupar, at the age of 66. There was no public mourning, no ceremony, no sympathy — only a sense of grim closure.

For many Colombians, his death marked the end of a living nightmare, though not the end of its echoes. Families of victims said they felt relief, but not justice. “He took our children, and he died without truly paying,” one mother said during a televised interview.

The Legacy of Terror: Lessons from the World’s Most Prolific Serial Killer

The case of Luis Garavito, the Colombian child serial killer, reshaped both law enforcement and criminological understanding in Latin America. Before his arrest, Colombia had no unified database of missing children, no specialized investigative unit for serial crimes, and minimal forensic coordination across departments.

After the Garavito case, Colombia launched reforms to strengthen national identification systems, improve interdepartmental communication, and expand child protection laws. The Ministry of Defense also established better coordination between the National Police and Prosecutor’s Office, specifically for pattern-based crime detection.

On a global level, criminologists began referencing Garavito alongside notorious figures such as Ted Bundy, Andrei Chikatilo, and Pedro López, often describing him as the “world’s most prolific serial killer.” His confirmed number of victims exceeded that of any known murderer in modern history, cementing his place in the darkest chapters of criminology.

Moreover, his story became a tragic symbol of how poverty, neglect, and systemic failure can create both victims and monsters. The thousands of displaced children in Colombia during the 1990s were invisible to the system — and in that invisibility, Garavito found his opportunity.

Books, Documentaries, and Continued Fascination

Numerous documentaries and books have since explored Garavito’s crimes and psychology. Some of the most notable include “The Beast of Colombia”, “Serial Killers of South America”, and Netflix’s true-crime series on Latin American criminals, all of which revisit his case as both a study in horror and a cautionary tale.

Journalists and criminologists continue to debate whether his estimated number of victims might be closer to 300 or even 400, given that many regions lacked records or were under conflict during his spree. Despite his death, Luis Garavito’s name remains synonymous with unimaginable evil, and his legacy continues to shape how societies confront the intersection of trauma, justice, and redemption.

FAQs: Everything You Need to Know About Luis Garavito

Who was Luis Garavito?

Luis Alfredo Garavito Cubillos, born on January 25, 1957, in Génova, Quindío, was a Colombian serial killer responsible for what is believed to be the highest confirmed number of murders in modern history. Known by his nickname “La Bestia” (“The Beast”), Garavito preyed upon young boys across Colombia, deceiving them with promises of food, education, or money before subjecting them to horrific torture and murder.

He is considered one of the world’s most prolific serial killers, with investigators confirming over 138 victims, though estimates range from 150 to more than 300. His crimes, uncovered in the late 1990s, stunned Colombia and the world for their brutality and scale.

How many victims did Luis Garavito kill?

Officially, Luis Garavito confessed to 138 murders, but investigators believe the true number is much higher — possibly 300 or more. Many disappearances during the 1990s went unreported due to Colombia’s civil conflicts and displacement crises. Forensic evidence, geographic mapping, and Garavito’s own confessions suggested he operated across nearly 11 departments in Colombia, often targeting street children, orphans, and runaways.

His victims were predominantly boys aged 6 to 16, selected for their vulnerability. His precise recollection of details — such as the color of a victim’s shirt or location of burial — convinced police that his confessions were genuine.

How was Garavito finally caught?

Garavito was captured in 1999 after a trail of evidence linked him to the murder of a young boy near Pereira, Colombia. At the crime scene, police discovered personal belongings including a pair of glasses, a receipt, and a notebook containing coded notes.

When forensic teams matched these items to a man frequently seen near missing children, authorities arrested Garavito under a false name, “Bonifacio Morera Liscano.” During interrogation, confronted with mounting forensic and witness evidence, he confessed in chilling detail to dozens of murders.

His arrest was the result of persistent detective work across several police units — a remarkable feat considering Colombia’s limited investigative resources at the time.

What happened during his trial?

Garavito’s trial in 2000 became one of the most closely watched legal proceedings in Colombian history. He was charged with multiple counts of murder, kidnapping, and sexual assault, based on confessions, witness statements, and physical evidence.

In court, he appeared composed, at times tearful, expressing remorse and claiming religious repentance. But prosecutors described him as manipulative and calculating, noting how he cooperated only when it benefitted him.

Ultimately, Garavito was convicted for 138 murders, with a total sentence of 1,853 years and 9 days — a symbolic figure reflecting the scale of his crimes. However, under Colombian law, the maximum effective sentence was capped at 40 years, later raised to 60 years for similar crimes.

His cooperation in locating burial sites earned him minor sentence reductions, but public outrage ensured he would never be eligible for release in practice.

What was Luis Garavito’s prison sentence?

Luis Garavito’s cumulative sentences added up to more than 1,800 years, the longest ever recorded in Colombia. Due to national law, this sentence was legally reduced to 40 years, though his status as a high-risk offender made him ineligible for parole or early release.

He served his time in a maximum-security facility in Valledupar, under constant protection due to multiple threats from other inmates. Several attempts were made on his life, forcing authorities to isolate him for long periods.

Is Luis Garavito still alive?

No. Luis Garavito died on October 12, 2023, at the age of 66, while serving his sentence. He passed away in a hospital in Valledupar, Colombia, after battling leukemia and other health complications.

His death marked the end of a 25-year imprisonment that never once saw him forgiven by the public. There were no ceremonies or family acknowledgments — only statements from victim advocacy groups and government officials reaffirming that “justice was served through confinement, not redemption.”

Why is he called “La Bestia” (The Beast)?

The name “La Bestia” was given by Colombian media and locals who could not comprehend the scale and cruelty of his crimes. Each murder revealed acts of deliberate torture, sexual assault, and psychological terror — atrocities that surpassed ordinary criminality.

The nickname symbolized not just his individual evil but also the national horror that gripped Colombia when the truth emerged. Over time, “La Bestia” became synonymous with both monstrous human behavior and institutional failure — a cautionary emblem of how neglect and social decay can breed unimaginable violence.

Could Garavito ever be released?

Technically, under Colombia’s laws prior to 2015, prisoners could apply for sentence reductions after serving a portion of their term and demonstrating “good behavior.” When reports surfaced that Garavito might qualify, public outrage exploded.

The Luis Garavito release controversy prompted national protests and government interventions. Legal experts and politicians confirmed that, despite any technical eligibility, he would never be freed due to the nature and magnitude of his crimes. His psychological evaluations classified him as “permanently dangerous.”

The uproar led to legal reforms, increasing maximum penalties for serial murderers and sexual predators to 60 years, effectively ensuring no such release could happen again.

Are there documentaries or books about Luis Garavito?

Yes. Garavito’s case has been the subject of numerous documentaries, investigative reports, and criminology books worldwide. Some notable ones include:

- “The Beast of Colombia” – a documentary analyzing the police investigation that led to his arrest.

- “Serial Killers of South America” – a true-crime anthology detailing how figures like Garavito and Pedro López operated amid social collapse.

- Various episodes in Netflix’s “World’s Most Evil Killers” and Discovery’s “Inside the Mind of a Monster” explore his psychology and crimes in detail.

Books and academic studies continue to cite Garavito as a case study in extreme psychopathy, demonstrating how trauma, opportunity, and systemic neglect converge to create predatory behavior.

The Broader Reflection: Lessons from “The Beast”

Luis Garavito’s crimes did not occur in isolation — they were a symptom of a deeper social sickness. Colombia in the 1990s was a nation torn by poverty, displacement, and conflict. Thousands of children lived without parental care, government oversight, or protection. Garavito thrived in that environment, exploiting the invisibility of society’s most vulnerable.

His story underscores how evil often hides behind normality — he smiled, joked, sold goods, and blended seamlessly into the chaos. It’s a chilling reminder that monsters rarely look like monsters.

From a psychological and sociological perspective, the Luis Garavito serial killer case pushed criminologists to question how early trauma, environment, and lack of intervention can spiral into full-blown sadistic compulsion. The case became central to studies in criminal profiling and forensic psychology, especially concerning child-targeted serial crimes.

Legally, Garavito’s actions forced Colombia to reform its penal and child protection systems, leading to stronger punishment for sexual violence and improved inter-agency cooperation for missing children.

But beyond the policy changes, the moral question remains — can a society ever truly reconcile with such horror?

Garavito’s death brought closure but not peace. For the families, justice felt incomplete; for the nation, the scars remained. His name will forever be etched into Colombia’s collective memory as both a warning and a wound — proof that sometimes, justice can contain evil, but never erase it.

Conclusion: Remembering the Unseen

Luis Garavito was not simply a killer; he was a mirror reflecting the darkest potentials of humanity and the cracks within our systems of care and justice. His crimes remind us why vigilance, compassion, and accountability are not luxuries — they are necessities for protecting the powerless.

As Riya’s Blogs often emphasizes, telling these stories is not about glorifying evil, but understanding it — ensuring the world never forgets the victims behind the headlines. Behind every statistic lay a lost child, a shattered family, and a silent lesson in what happens when society stops watching.

Luis Garavito, La Bestia, may have died in prison, but the world he exposed — one of neglect, trauma, and the fragility of innocence — continues to demand our attention. And perhaps that is the truest form of justice we can still give to those he took.

Want to read a bit more? Find some more of my writings here-

Why Ghost Stories Are Universal Across Cultures

60 Anniversary Quotes to Celebrate Your Love Story

The Library at the End of Dreams: Dark Fantasy Short Story

I hope you liked the content.

To share your views, you can simply send me an email.

Thank you for being keen readers to a small-time writer.