Written by: Katyayani Mishra

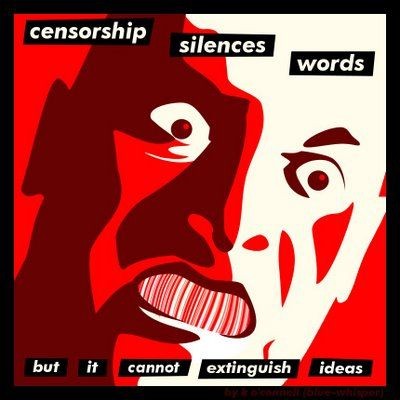

Censorship in Indian cinema is not a recent development. It never begins with an individual. While one person may not like the film or disagree with it, censorship involves a group of people who find a particular film to be objectionable or obscene, causing a ruckus in the way it’s been released for the masses to see. The Oxford Dictionary of English defines censorship as the suppression or prohibition of content that is considered to be obscene, politically unacceptable or a threat to security.

Cinema is a potent medium that stimulates thought and provides a platform for artistic and political expression. I wished that cinema was a form of escapism. It’s not. You remember the story, the message, the themes, even years later. It’s more than just an art form; it’s an emotion and a reflection of society. Indian cinema has long served as a cultural, political, and moral mirror displayed through its silver screen. Although it is influential, it is often subject to scrutiny and regulation.

Since the colonial period, censorship has been a tool used to regulate, moralise, and, often, act as an invisible hand to intimidate creativity. Censorship is not just about cut scenes and muted dialogues, but a quest for power between artistic freedom and comfort. Ironically, Indian cinema produces over 2,000 films a year, more than any other country, yet the freedom of expression is often under surveillance. The Indian film industry has witnessed continuous efforts by state and non-state actors to define what is “acceptable” for public viewing.

The Supreme Court of India once said, films demand stricter regulation because they hold our attention more powerfully than written words, and that’s perhaps the most honest admission of cinema’s influence on society.

Importance of Cinema

Globally, cinema has found its way into poorer societies. It’s been found to unite people throughout history. During the Great Depression (1918), society was distressed, grappling with inflation. Even in India (1939), when nationalist readings fell on deaf ears among British officials, seasonal cinemas and touring talkies were introduced. These built an engaging audience so strong in the realm of ramifying differences and contradictions that even when British officials broke down these touring talkies, the villagers somehow found ways to share their love for cinema. While it was only a show for the rich, the “poorer class” found more entertainment in watching cinema because it somehow reflected them- their angst, frustration and struggles. This connection can be drawn to Shakespeare’s plays, where the lower class enjoyed his plays because they found the stories relatable.

Colonial Influence

When cinema arrived in India in the early 1900s, the British saw more than mere amusement; they recognised a medium of influence. Moving images could stir emotion, awaken political consciousness, and kindle nationalist sentiment. Consequently, the colonial administration enacted the Cinematograph Act of 1918, empowering provincial governments to censor any film that might “excite disaffection.” Colonial administrators often viewed Indian audiences as incapable of rational engagement with film. British officials described them as “child-like,” “morally corruptible,” and “deficient in character,” mirroring the stereotypes of Indian subjects prevalent in imperial discourse. Such paternalistic assumptions underpinned the British Board of Film Censors’ (BBFC) interventions in India.

In one illustrative case from 1923, a film depicting an Englishman who offends a Native American woman and is ultimately tied to a post and left to die was met with applause by Indian audiences. This reaction alarmed colonial authorities, who feared that such scenes would incite hatred toward the British Empire.

What they failed to grasp, however, was that Indian resentment toward colonial rule already existed; cinema merely provided a channel through which that suppressed anger found symbolic expression. By the 1920s, movie theatres had become spaces where Indians could translate political frustration into collective emotion, reclaiming cinema as both art and subtle resistance.

Post-Independence Censorship

The Cinematograph Act of 1952 established the Central Board of Film Certification (CBFC). Its initial purpose was straightforward: classify films according to suitability. However, over the decades, it evolved into a moral authority, policing not just what was watchable, but what was thinkable.

The Emergency (1975-1977) AND CENSORSHIP IN MASS MEDIA

The State had declared “Emergency” in 1975 by the then Prime Minister, Mrs Indira Gandhi. It prevented all forms of mass media that could possibly represent the government and its policies in a negative light. Similar to how we had seen in Germany during Hitler’s reign, where every form and medium of expression was heavily under the government’s scrutiny. Even now, we see how the media in our country is still a victim of such control. While, at the time, the supreme control was in the hands of the state, it sought to guarantee or prohibit meanings which resulted in information in the form of magazines and fliers being spread against her government. Thus, in 1977, when she called for elections and lost to her opposition leader, Moraji Desai, it was concluded by some that she was unaware of the public’s discontent and anger. During the emergency period, it wasn’t only films like “ Kissa Kursi ka” The film made a mockery of Sanjay Gandhi’s auto-manufacturing plans. The film was submitted to the Censor Board for certification in April 1975. The master prints and all copies were lifted from the Censor Board office and burnt, but also songs from Kishore Kumar, the legendary singer, that were banned because he refused to sing in praise of her government. It vividly illustrated the complete vulnerability of cinema to pressures exerted by the central government, revealing how easily artistic expression can be distorted when decisions stem from personal biases, individual agendas, or narrow political interests.

The political influence on films still tends to prevail. Udta Punjab (2016) more recently Phule (2025), became popular because both the films portrayed the problems too realistically. Udta Punjab highlighted the drug problem, and Phule showcased casteism. It’s ironic how we expect cinema to act as a mirror, and we go outright mad when it actually portrays the truth on screen.

Sex, Religion & History- A societal taboo

Films are usually attacked and censored for one of the six reasons: sexuality, politics, religion, communal tensions, incorrect portrayals of public figures, or extreme violence.

Satyajit Ray’s Devi (1960) exemplifies the fraught relationship between cinema, faith, and societal sensitivity. The film was condemned by conservative groups for being “offensive,” even though Ray’s intent was not to attack religion itself but to critique the dangers of blind faith and ritualistic dogmatism. Decades later, Aamir Khan’s PK (2014) triggered a similar national debate on religion and fanaticism. Accused of mocking faith, the film faced boycott calls and vandalism of theatres, yet its central argument questioning the commercialisation of religion and the manipulation of belief was profoundly humanistic rather than irreverent.

In contrast, The Kerala Story (2023) attracted criticism for allegedly distorting facts and reinforcing divisive narratives under the guise of realism. Public outrage in this case took an opposite form: where Devi and PK were censured for their dissent, The Kerala Story was scrutinised for its perceived propaganda. Together, these examples reveal how the boundaries of censorship are constantly redrawn by shifting political climates and societal sensibilities, where offence can stem as much from uncomfortable truths as from contested representations of truth itself.

Raj Kapoor’s Satyam Shivam Sundaram (1978) became one of the most controversial films of its time, provoking intense debate over morality and representation. Much of the film’s publicity and press coverage focused not on its philosophical premise but on Zeenat Aman’s sensual portrayal. Promotional posters and hoardings highlighted her physicality, showing her in low-cut cholis or a sequined white outfit, fueling public accusations of obscenity and vulgarity. This outrage, however, appears puzzling when viewed against the broader cinematic context of the period, which openly accommodated sex-education films, soft-core erotica, and adult-themed narratives.

At its core, the film explores the relationship between truth, beauty, and divinity that are deeply embedded in Indian cultural philosophy. The devotional songs rendered by Lata Mangeshkar underscore this spiritual dimension, allowing Kapoor to argue that his film was a moral allegory rather than an indulgent spectacle. He took his dispute with the Central Board of Film Certification (CBFC) to court, asserting that their proposed cuts, particularly the scenes involving sensuality. It would destroy the film’s “soul.” Ironically, the element deemed objectionable by the censors, the body, was precisely what Kapoor positioned as the film’s spiritual essence.

The CBFC’s decision to excise specific scenes revealed a narrow reading of morality, ignoring the complex duality Kapoor sought to portray. Zeenat Aman’s character embodies both purity and sensuality, reflecting an authentic depiction of the Indian feminine ideal draped in a saree, unapologetically human, and spiritually radiant. Her physical imperfection, shown with empathy, symbolised the reconciliation of inner beauty and outer truth. Highlighting such realism was deemed indecent, exposing the cultural contradiction between India’s spiritual heritage and its modern conservatism.

The irony lies in the fact that the very content censored for being “vulgar” was meant to provoke reflection on the unity of the sensual and the sacred ideal in Indian aesthetics. Rather than distorting morality, Kapoor was reclaiming it, challenging the artificial divide between spirituality and physicality. In doing so, Satyam Shivam Sundaram stands as a visionary critique of censorship itself. It was a film that questioned how far society is willing to go to silence its own truths under the guise of protecting them.

Padmaavat, directed by Sanjay Leela Bhansali, ignited widespread controversy for its depiction of historical and cultural themes, particularly those surrounding the Rajput queen Padmavati and the Muslim ruler Alauddin Khilji. The film faced allegations of distorting history and offending Rajput pride, primarily due to rumors of a romantic relationship between Padmavati and Khilji and specific dialogues that were deemed derogatory. These accusations provoked intense public debate about the tension between artistic freedom and historical accuracy, with many seeing the film as misrepresenting cherished cultural icons.

Even before the film’s release, the Karni Sena- a Rajput caste-based organisation- responded with violence by vandalising the film’s set, assaulting Bhansali, and issuing threats against the lead actress Deepika Padukone, including threats to chop off her nose as a symbolic act reminiscent of the Ramayana’s Surpanakha. Protests rapidly spread across several states, including Uttar Pradesh, Haryana, and Rajasthan, with some political figures offering bounties for violent acts against the filmmakers.

Due to escalating tensions, the producers sought judicial protection, and the Supreme Court ultimately ruled that states could not ban the film based on subjective community sentiments, affirming that cinema is an inseparable part of the right to free speech and expression. Despite this, political leaders continued to call for changes to ensure that no community’s sentiments would be hurt, highlighting how mob pressure and political concerns can threaten both the creative process and constitutional freedoms, regardless of the film’s actual content.

Censorship & Protection of Nationalism

Censorship in India often reflects the current political climate. A notable example is the 2016 controversy surrounding Karan Johar’s film “Ae Dil Hai Mushkil”, which starred Pakistani actor Fawad Khan. In the wake of the Uri attack and escalating political tensions, the Maharashtra Navnirman Sena (MNS) threatened to block the film’s release unless Pakistani actors were removed. Although the Central Board of Film Certification (CBFC) had already granted the film approval, political pressure led Johar to issue a public apology and promise not to collaborate with Pakistani artists in the future. The film was centred around relationships and had nothing to do with Fawad Khan’s nationality, yet the film faced several cuts in the scenes that involved his character.

Bollywood, for long as an industry has accepted people from several other countries, Katrina Kaif (our Barbie girl), Nora Fethi aren’t Indian yet audiences love their performances and they have a huge fan base. Art has always been unifying. Despite several such backlashes, cinema continues to prevail with stories and themes that are thought-provoking and touching. At the end of the day, art can have several meanings. One song, film, or any other piece of literature can be analysed and interpreted in several ways that may or may not align with your personal opinion, but that doesn’t mean it’s wrong.

Conclusion

I’m a movie buff, and I’ve loved films ever since I can remember. They captivate me and make me feel like I belong in the story. As an artist myself, I can say that art is political; it is supposed to make you feel uncomfortable.

Although the entertainment value of film has become more prominent, its capacity to provoke thought and disseminate critical viewpoints endures. What has changed, however, is the locus of surveillance, using more nuanced mechanisms to influence the boundaries of permissible discourse. Modern censorship rarely acts through overt punishment; rather, it subtly restricts content and shapes societal norms and values.

Despite these constraints, new filmmakers and artists continue to innovate, circumventing rigid norms through creative storytelling and symbolic protest. Their work demonstrates that the spirit of resistance and the pursuit of dialogue through cinema persist, always finding new ways to narrate dissent and move beyond the confines of censorship.