Written by: Katyayani Mishra

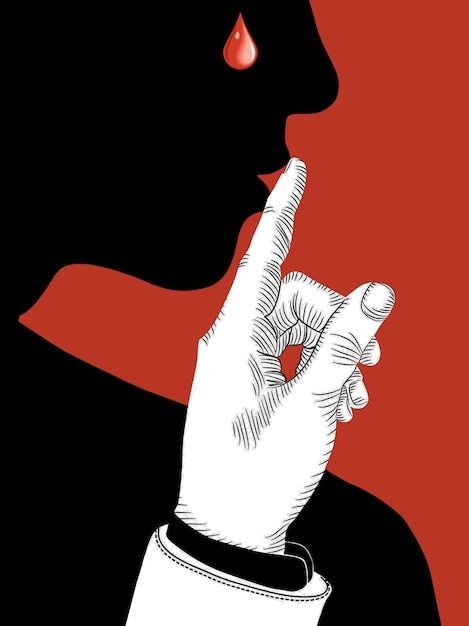

I’ll call this a silent manipulator of the popular culture. As much as I love crime and thrillers, and as much as we enjoy them, it is influential to a wider population. As we are hungry for emotional intensity, we overlook the power it can hold on some viewers who may take inspiration from such films or web series. Most people remain unaware of how deeply this glorification influences their daily thoughts, shaping their fears, aspirations, and attitudes without their explicit awareness. We often forget to question the moral cost of such entertainment.

Movies, television series, music, and even podcasts often portray brutality as heroic. Unless you find other forms of art that question societal norms. The glorification of crime, war, and violence is one of the most overlooked yet widespread influences in modern popular culture. What makes this trend concerning is not just its prevalence, but its subtle power. These depictions quietly infiltrate our collective consciousness, changing the way we view justice, morality, and even humanity itself. As a society, we like to believe we are in charge of the media we consume, but it is the media that shapes us. And, unless we stay self-aware and deliberate in our consumption, we risk losing sight of our own values in the haze of unrealistic, romanticised violence.

The question is, why are we so captivated by these narratives?

Humans have a natural tendency to respond to drama, conflict, and danger. This stems from psychological factors: movies capture our attention by stylising violence and glamorising criminals, which makes us like moths drawn to a flame.

In folklore, the anti-hero was always intriguing. In modern media, the criminal is portrayed as a mastermind. As The Hindu states, many films repeatedly glorify gangsters, portraying them as Robin Hood-like figures or misunderstood rebels, which makes them into icons and their crimes into narratives of valour. Even notorious criminals in India have found their reputations rehabilitated through cinema, transformed into folk heroes rather than cautionary tales. Even when their real-life counterparts inflict genuine harm on communities and society.

The present generation is often accused of being more vulnerable due to greater media exposure, leaving them at a higher risk of being influenced. Every generation, from the Western era and war propaganda films to modern streaming thrillers, has been shaped by the cultural narratives of violence available to them. The scale today is wide because of global access and endless content.

The Filmmaker’s Intentions

The film industry rarely acknowledges its ethical missteps. Creators often defend violent content as “realism,” “artistic freedom,” or a “reflection of society.” Films like Animal or Kabir Singh are particularly problematic as they portray toxic masculinity on screen and justify male violence and aggression. Nonetheless, studios rationalise these portrayals by pointing to box office success, violence, crime, and war tend to attract larger audiences. However, there exists a moral grey area that cannot be overlooked. The question: do they intend harm? The Guardian has reported that policymakers have questioned whether producers genuinely consider the repercussions of glorifying brutality, particularly when such content can shape public perceptions and behaviours. While most filmmakers do not intend to cause harm, intent is no longer the primary concern; the impact of their work is what truly matters. Critics argue that the constant glorification of brutality can lead to imitative behaviour, especially among youth.

Some actors enjoy portraying dangerous characters, while others feel uncomfortable with how their roles are later romanticised. Creators may not aim to negatively influence society, but once their work reaches the public, they cannot claim neutrality. Representation is inherently biased. Few creators openly acknowledge the negative social impact of their work, and even fewer modify their projects in response to such concerns. This ethical dilemma becomes a tug-of-war between artistic ambition, market demand, and public responsibility.

The Dilemma between Creative Freedom & Societal Consequences

One of the greatest ethical dilemmas today is the tension between creative freedom and societal harm. Should filmmakers curb artistic expression to protect viewers? Or should society accept violence as part of storytelling? Realism is often the shield used to justify graphic content.

Consider war movies. As The Ringer notes in its critique of films like 1917 and Saving Private Ryan, even the most “authentic” war portrayals inevitably become stylised. The camera’s beauty aestheticises the battlefield. Horror becomes choreography. Destruction becomes spectacle.

But for those who have lived through war, such portrayals can feel deeply discordant. They reduce geopolitical tragedies into simple binaries: heroes and villains, victory and loss. They flatten trauma into entertainment. They romanticise courage but rarely show the lifelong cost.

The audience, in turn, begins to see war not as a catastrophic failure but as cinematic glory.

Nature vs Nurture

Popular culture acts as both a mirror and a mould, shaping our society for a long time since it became a widespread phenomenon. Some people are naturally more susceptible to media influence than others. This susceptibility can be influenced by genetics; for instance, certain personality types may be more impulsive, impressionable, or thrill-seeking. Additionally, environmental factors, such as family background, trauma history, peer pressure, and exposure to violence, further shape an individual’s vulnerability.

Individuals who struggle with stable emotional regulation or have weak identity formation are more likely to internalise the messages conveyed by popular culture. For example, a child raised in an unstable home, a teenager with low self-esteem, or an adult surrounded by aggression may absorb media messages without the ability to critically assess them. For these individuals, violent protagonists are not merely fictional characters; they become templates for behaviour, power, and identity. In a society saturated with stylised violence, this can be especially dangerous for impressionable minds, who may confuse harmful behaviour with glamour, rebellion, or power.

Representations in Films

The media doesn’t influence everyone equally. Violent or crime-glorifying films can impact cultural and racial groups. Representations of certain races or communities as criminals can reinforce stereotypes, creating bias both inside and outside those communities. Conversely, members of marginalised groups may internalise these portrayals, shaping their identity around dangerous media narratives.

For example, when serial killers like Ted Bundy are romanticised, as highlighted in The Cowl, the phenomenon disproportionately affects female audiences, who may begin to view dangerous individuals through a warped, glamorised lens. This proves how the media not only stereotypes groups but also shapes dangerous patterns of attraction or empathy.

Can we solve the problem?

Solving the problem of negative mass influence from popular media requires more than isolated efforts; it demands a cultural shift driven by awareness, responsibility, and accountability at every level. The goal is not to censor creativity, but to cultivate consciousness: a collective understanding that the stories we tell and consume shape the society we live in. A multi-layered, deeply collaborative approach can help reduce harm while preserving the integrity of artistic freedom. Reducing harm from violent media is not about silencing creativity; it is about fostering an environment where creators and consumers share mutual awareness. When filmmakers adopt ethical storytelling, when audiences develop critical thinking, and when institutions put protective systems in place, we cultivate a culture where art stays powerful but does not cause harm. Art shapes society, but society, through conscious engagement, can shape art right back.

1. Prioritising Media Literacy from an Early Age

Media literacy is the cornerstone of resilience against harmful influence. When young people learn to critically analyse the content they consume, identifying narrative framing, moral ambiguity, and bias, they become far less susceptible to manipulation. This education should be woven into school curricula, not as a moral lecture but as a skill set: the ability to question images, decode symbolism, and distinguish fiction from endorsement. An audience that thinks critically is harder to mislead, glamorise, or emotionally sway.

2. Encouraging Ethical and Responsible Filmmaking

Filmmakers wield immense cultural power, and with that comes ethical responsibility. Ethical filmmaking does not mean sanitising reality; it means portraying violence with the gravity it deserves. Instead of unnecessary aestheticisation, slow-motion action sequences, glorified criminals, or stylised bloodshed, creators can choose to highlight consequences, context, and emotional depth. Violence can remain part of storytelling without being turned into spectacle. When creators treat these themes with respect, audiences begin to do the same.

3. Strengthening Content Warnings and Rating Systems

A robust rating system is not merely a bureaucratic formality; it is a protective filter. Accurate age ratings, detailed content warnings, and transparent descriptors help parents, educators, and viewers make informed decisions. Vulnerable audiences, especially children and adolescents, should never stumble unknowingly into violent or crime-glorifying content. Stronger, clearer classifications act as the first line of defence, ensuring that exposure is intentional rather than incidental.

4. Promoting Balanced and Nuanced Storytelling

Art does not need to avoid violence; it needs to contextualise it. Balanced storytelling ensures that films do not present crime, war, or brutality in isolation from their consequences. Showing the impact, the trauma, the ethical dilemmas, and the destruction that follows creates a more holistic understanding. When war films highlight not only battlefield heroism but also its psychological and societal aftermath, when crime dramas show the victims as vividly as the perpetrators, audiences learn to distinguish realism from romanticisation.

5. Offering Alternative Narratives and Diverse Storytelling

An industry driven by formulaic violence risks stifling creativity. Promoting alternative narratives, stories centred on resilience, community, empathy, and conflict resolution, broadens the imaginative landscape. Audiences deserve stories that challenge, inspire, and heal, not just those that shock or sensationalise. When the market supports such diversity, the cycle of glorified violence weakens.

6. Strengthening Social Accountability and Audience Responsibility

Consumers hold more power than they realise. Every view, stream, and ticket purchased signals demand. When audiences push back. Rejecting glamorised brutality, calling out irresponsible portrayals, or supporting films with thoughtful representation, the industry pays attention. Social accountability means encouraging conversations rather than passively absorbing content. The more we discuss how the media affects us, the more we collectively disarm its negative influence.

Conclusion

The glorification of crime, war, and violence is far from harmless entertainment; it is a cultural force woven into the fabric of modern life. Humans are, after all, hardwired to notice danger. Our evolutionary instincts draw us towards conflict, whether real or fictional. Crime dramas tap into our primal fascination with threat; war films dazzle us with spectacle, playing on deep psychological patterns of survival, loyalty, and heroism. Today, however, our vulnerability runs deeper. This generation does not encounter violence in measured doses but as a constant, curated backdrop. From noir thrillers to hyperrealistic battle epics, the imagery is relentless: algorithmically delivered, endlessly accessible, and difficult to escape. While every era has had its share of violent entertainment, ours is the first to consume it across every platform, every hour, every scroll.

In such perpetual immersion, the line between entertainment and empathy begins to erode. As The Hindu reports, even notorious criminals in India have seen their reputations softened through cinema, recast as folk heroes instead of cautionary tales. The question is no longer why such stories exist, but why we are so irresistibly drawn to them, and what happens when fascination quietly slips into admiration.

This is where the real danger lies. When violent narratives seduce us without restraint, they start shaping us in ways we do not always recognise. The stories we consume influence our moral compass, our understanding of justice, and our perception of heroism. Entertainment should stir emotion, not numb compassion; provoke thought, not promote harm. The responsibility is not to reject artistic expression but to understand its power. If we engage with media consciously, without surrendering to its seductions, we protect our identities, values, and shared humanity. Popular media will always influence us, but with awareness, intentionality, and ethical storytelling, that influence can enlighten rather than distort, empower rather than endanger. Ultimately, the real threat is not the violence shown on screen but the violence we cease to notice.