Introduction

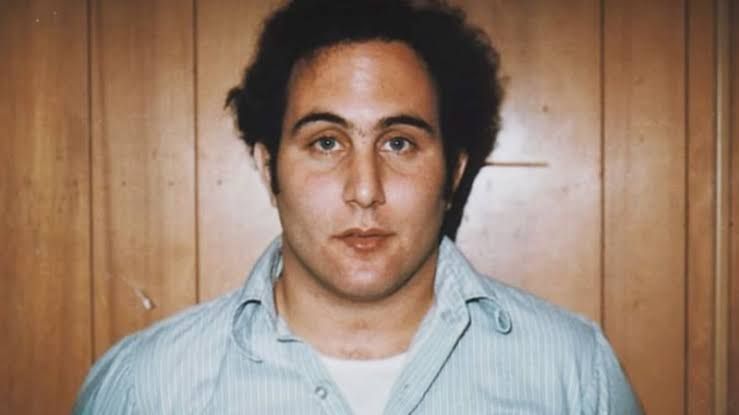

Between 1976 and 1977, New York City was gripped by fear. Headlines screamed of the “Son of Sam shootings,” a series of brutal and random attacks that left six people dead and seven others wounded. The perpetrator was David Berkowitz, a man whose crimes, confessions, and letters to police reshaped the psychology of serial killer investigations in America. His story remains one of the most haunting chapters in the history of modern crime — not just for its brutality, but for the way it intertwined violence, media, and madness.

This article from Riya’s Blogs dives deep into the life, crimes, and psychology of David Berkowitz — the man the world came to know as the Son of Sam.

Early Life and Background

David Richard Berkowitz was born on June 1, 1953, in Brooklyn, New York. Adopted shortly after birth by Nathan and Pearl Berkowitz, he had what seemed like an ordinary childhood — but underneath, he harbored growing feelings of abandonment and rage. His biological mother had given him up due to financial hardship, a fact he would later obsess over.

Teachers described him as bright but troublesome. He showed early signs of aggression and fascination with fire, both red flags often observed in psychological profiles of violent offenders. After graduating high school, Berkowitz joined the U.S. Army and served in South Korea, returning to New York in 1974. He lived alone, working as a postal worker — an unremarkable man, hiding a storm inside.

By 1976, that storm would explode into violence, giving birth to one of the darkest episodes in New York’s history: the Son of Sam shootings.

The Son of Sam Shootings (1976–1977)

The Son of Sam shootings began in the summer of 1976. The first attack occurred on July 29, when two young women sitting in a car in the Bronx were shot with a .44-caliber revolver. One of them, Donna Lauria, was killed instantly. Over the next year, the shootings continued across the boroughs — Bronx, Queens, and Brooklyn — targeting mostly young women with long, dark hair and their boyfriends sitting in parked cars.

The randomness of the attacks paralyzed New York. Police connected the crimes through ballistic evidence — all bullets were from the same .44-caliber Charter Arms Bulldog revolver. Newspapers dubbed the killer “the .44 Caliber Killer,” before Berkowitz himself provided a new name through his letters.

Each shooting brought new victims and new panic:

- Donna Lauria (18) – killed July 1976

- Christine Freund (26) – killed January 1977

- Virginia Voskerichian (19) – killed March 1977

- Valentina Suriani (18) and Alexander Esau (20) – killed April 1977

- Stacy Moskowitz (20) – killed July 1977

Several others were wounded, leaving behind a trail of trauma and shattered lives. The David Berkowitz victims list became a grim catalog of fear.

By early 1977, New York City was a city under siege — couples avoided sitting in cars, women cut their hair short or dyed it blonde, and the NYPD launched one of the largest manhunts in American history.

The Letters to Police: Taunting the City

In April 1977, police found a chilling letter near the bodies of Suriani and Esau. Written in a bizarre, mocking tone, it was addressed to NYPD Captain Joseph Borrelli, and signed “Son of Sam.” The killer wrote about a “Father Sam” who commanded him to kill — a delusional justification that added a satanic and psychological dimension to the case.

Another Son of Sam letter was sent directly to newspaper columnist Jimmy Breslin, who published it in the New York Daily News. The letter was both taunting and strangely articulate, filled with references to demons and commands from his “father.” It captivated the public, transforming Berkowitz into a media phenomenon.

The Son of Sam letters to police remain among the most infamous correspondences in criminal history — a blend of paranoia, theatrics, and manipulation that showcased Berkowitz’s desire for attention and control.

The Arrest and Confession

On August 10, 1977, after a year of panic, David Berkowitz was arrested outside his Yonkers apartment. The break came from a parking ticket issued near the scene of the final shooting — a small clue that led detectives straight to him.

When police approached, Berkowitz allegedly said, “You got me.” Inside his car, they found the .44-caliber revolver, maps of crime scenes, and another threatening letter addressed to authorities.

During interrogation, Berkowitz confessed to all eight shootings, claiming that a demon — speaking through his neighbor Sam Carr’s dog — commanded him to kill. This bizarre narrative only deepened public fascination, turning his case into a study of the criminally insane.

The David Berkowitz trial and confession quickly followed. He pled guilty to all charges, sparing New York a prolonged trial. In 1978, he was sentenced to six consecutive life sentences, ensuring he would never walk free again.

Psychology and Profile of David Berkowitz

Psychiatrists diagnosed Berkowitz with paranoid schizophrenia and antisocial personality disorder, but many experts believe he was fully aware of his actions. His psychology profile suggested a man driven by loneliness, delusion, and a craving for recognition.

He exhibited the “triad” often linked with serial offenders — cruelty to animals, fire-setting, and social isolation. His confessions revealed a blend of supernatural beliefs and deep resentment toward women, particularly those who reminded him of his biological mother.

Forensic psychologists studying David Berkowitz’s psychology profile note his meticulous planning, alternating with erratic behavior, as signs of psychopathy rather than pure insanity. Even in prison, he would later alternate between remorse and religious preaching, keeping psychologists divided over whether he had truly reformed.

Life in Prison

In prison, David Berkowitz’s prison life took an unexpected turn. Initially, he faced numerous attacks from other inmates — one even slashed his throat, leaving a permanent scar. Over the years, Berkowitz claimed to have “found God” and began calling himself the “Son of Hope.”

He became a born-again Christian, counseling other inmates and writing letters of remorse to victims’ families. However, critics remain skeptical, believing his transformation is more self-preservation than repentance.

Berkowitz has been denied parole multiple times — the last known hearing in 2022 reaffirmed that he will likely die behind bars. Today, David Berkowitz resides at Shawangunk Correctional Facility in New York.

The Son of Sam Law

One of the most enduring legacies of the case is the Son of Sam Law New York, enacted in 1977. This law prevents criminals from profiting from their crimes through books, movies, or media deals. It was passed after Berkowitz received massive media attention, and publishers sought exclusive rights to his story.

While the Son of Sam Law faced multiple constitutional challenges, it became a model for similar laws across the United States — a moral boundary ensuring that murderers could not turn their infamy into financial gain.

Media Influence and Cultural Impact

The Son of Sam shootings forever changed how the media covered crime. The constant front-page coverage, speculation, and public panic led to what many call the first modern “media serial killer frenzy.”

- Spike Lee’s film “Summer of Sam” (1999) dramatized the paranoia and chaos of that summer, blending fiction and reality.

- Copycat shooters in the 1980s tried to emulate Berkowitz’s style of random attacks, proving the lasting psychological impact of his crimes.

- The Netflix documentary “The Sons of Sam: A Descent Into Darkness” (2021) revisited conspiracy theories about multiple shooters, questioning whether Berkowitz acted alone.

- The New York “Son of Sam law” directly emerged from the case’s media aftermath, forever tying crime, fame, and ethics together.

From 1976 to 1977, New York’s descent into fear and sensationalism shaped how future criminal investigations, media coverage, and psychological studies of serial killers would unfold.

FAQs

Who was David Berkowitz?

David Berkowitz, also known as the “Son of Sam,” was an American serial killer who terrorized New York City between 1976 and 1977, killing six people and wounding seven others.

Why was he called the “Son of Sam”?

He called himself “Son of Sam” in letters to police, claiming his neighbor’s dog, owned by a man named Sam Carr, was possessed by a demon that ordered him to kill.

How many people did Berkowitz shoot?

In total, Berkowitz shot 13 people, killing six and injuring seven.

How did Berkowitz taunt police with letters?

He wrote letters mocking police and the press, calling himself “Son of Sam,” and promising further violence. These letters were left at crime scenes or mailed to newspapers.

When was Berkowitz arrested?

He was arrested on August 10, 1977, outside his Yonkers apartment after detectives traced a parking ticket near a crime scene to his car.

What happened during his trial?

He pled guilty to all charges and was sentenced to six consecutive life terms in prison.

Is David Berkowitz still alive?

Yes, as of 2025, he remains alive and incarcerated in New York.

What is the “Son of Sam law”?

It is a law preventing criminals from profiting from their crimes through media or book deals, enacted after Berkowitz’s case.

Has Berkowitz ever spoken about his crimes in prison?

Yes. He has given interviews expressing remorse and claims to have become a Christian, calling himself the “Son of Hope.”

Media Frenzy in New York: How the “Son of Sam” Consumed an Entire City

The Son of Sam shootings (1976–1977) didn’t just terrorize New York City — they rewired its psyche. The fear wasn’t confined to the victims; it seeped into the rhythm of daily life, shaping how people dressed, traveled, and even fell in love. David Berkowitz’s crimes were horrific on their own, but the way they were reported magnified their psychological impact to an almost mythic level. For the first time in modern America, the killer and the media fed off each other in real time.

By late 1976, the city was already anxious — facing financial ruin, rising crime rates, and widespread mistrust in government institutions. When the David Berkowitz crimes in New York began, newspapers and TV stations found a story that combined horror, mystery, and shock value. Headlines screamed “The .44 Caliber Killer Strikes Again!” and “Young Lovers Gunned Down.” The press coverage became relentless — not just chronicling the case, but sensationalizing it.

The Son of Sam letters to police gave journalists what they craved most: drama. The chilling tone, bizarre references to demons, and the self-bestowed moniker “Son of Sam” transformed Berkowitz from an anonymous gunman into a household name. It was one of the earliest examples of how the media could turn a murderer into a celebrity — something that would later become a controversial ethical dilemma in crime reporting.

Newspapers like the New York Daily News and New York Post published the letters in full, increasing public panic. Circulation numbers skyrocketed, and newsstands sold out within hours. Nightly newscasts opened with updates about the killer’s next possible move. In essence, the Son of Sam shootings became New York’s first live, serialized crime drama — one that blurred the line between news and entertainment.

People across the five boroughs began altering their lives. Women dyed their hair blonde to avoid fitting the killer’s “type.” Bars and discos emptied early, and lovers who once sat parked under city lights now drove home in fear. Taxi drivers refused to pick up lone passengers at night. The police department, overwhelmed and desperate, fielded over 200,000 tips — most of them useless, but all driven by hysteria.

Psychologists studying David Berkowitz’s psychology profile later argued that the media’s obsessive focus may have emboldened him. The killer watched his notoriety grow daily in the headlines; his words became front-page material. That attention, experts believe, gave him the validation he craved.

The media frenzy in NYC reached such intensity that Mayor Abraham Beame himself addressed the city on television, pleading for calm. The case redefined how law enforcement managed communication with the press — a practice that would later influence protocols in the cases of Ted Bundy, Jeffrey Dahmer, and other serial offenders.

Even after Berkowitz’s arrest, the fascination didn’t fade. Publishers, screenwriters, and documentary makers competed to retell the David Berkowitz Son of Sam story. The coverage turned the killer into a cultural figure — not of admiration, but of enduring morbid intrigue. His case exposed an uncomfortable truth: when crime meets celebrity, the audience can’t look away.

Copycat Crimes and the Dark Echo of “Son of Sam”

The chilling influence of David Berkowitz extended far beyond his arrest. The copycat shooters in the 1980s reflected how deeply his crimes penetrated public consciousness. Psychologists and criminologists noticed a disturbing trend — individuals inspired by Berkowitz began mimicking aspects of his behavior, weapons, or psychological justifications.

One of the earliest recorded copycats was a man in New York who began sending anonymous letters to newspapers claiming to be the “Son of Sam II.” He referenced the original shootings and threatened to resume the spree. Though it was quickly debunked, it highlighted how the David Berkowitz crimes in New York had left behind not just victims, but a cultural template for infamy.

Throughout the 1980s, police departments across the United States reported several cases of random shootings accompanied by cryptic letters or “mission” statements — echoing the Son of Sam letters to police. In Los Angeles and Chicago, investigators discovered that some of these perpetrators idolized Berkowitz’s notoriety. They viewed him not as a murderer, but as a symbol of rebellion against society.

This phenomenon gave rise to the term “media contagion effect” in criminal psychology. It suggests that intense coverage of violent crimes can inspire unstable individuals to imitate them — either for attention, power, or delusional fulfillment. The David Berkowitz Son of Sam narrative became a case study in every criminology course discussing copycat psychology.

Berkowitz himself would later express guilt over this legacy. In a 2006 prison interview, he said, “If I could take it all back, I would. I know people were hurt long after the shootings stopped — by others who tried to be me.” His remorse, genuine or not, acknowledged that the horror he unleashed didn’t end in 1977.

Law enforcement agencies began developing new media guidelines to prevent future contagion. Press conferences avoided glamorizing perpetrators. Journalists were urged to focus on victims rather than killers. Ironically, these reforms stemmed directly from the chaotic media handling of Son of Sam — proof that his crimes forced society to rethink how it tells stories of violence.

Even pop culture couldn’t resist referencing him. Songs, novels, and even stand-up comedians alluded to Berkowitz. The phrase “Son of Sam” became shorthand for evil hidden behind ordinary faces. In a twisted way, the Son of Sam shootings 1976–1977 created an archetype — the lonely, unnoticed man next door who suddenly becomes a monster.

The Law That Changed Everything: Understanding the “Son of Sam” Law

After the arrest, an unsettling discovery emerged: publishers and filmmakers were competing to buy Berkowitz’s story rights. The idea that a murderer could profit from his own crimes outraged the public. In response, the Son of Sam law in New York was passed in 1977. It empowered the state to seize any earnings from criminals who sold their stories to the media, redirecting that money to victims and their families.

The original version of the Son of Sam law was broad. Any payment made to a convicted felon for recounting their crimes — through interviews, books, or movie deals — would be held in escrow for five years. During that period, victims could file civil suits to claim the funds. The law reflected society’s moral stand that fame should never reward violence.

However, the law faced challenges. In 1991, the U.S. Supreme Court struck it down in Simon & Schuster v. Crime Victims Board, arguing it violated free speech rights. Critics claimed it unfairly targeted specific content — namely, crime stories. Still, the public outcry led New York to revise and narrow the law, ensuring it applied only when profits were directly tied to criminal acts.

The David Berkowitz Son of Sam case became a benchmark for media ethics. Even decades later, the law inspired similar legislation across other states. Some called it the “moral firewall” — a boundary between curiosity and exploitation.

Interestingly, Berkowitz never attempted to profit from his infamy. In later years, when approached for interviews, he refused payment, citing his faith and remorse. His prison life — now dominated by religion and reflection — stood in stark contrast to the chaos of his crimes. Yet the Son of Sam law New York remains his legal shadow, a reminder that some crimes reshape not only victims’ lives but society’s moral compass.

Cultural Reflections: Films, Documentaries, and the Legacy of Fear

The story of David Berkowitz has lived on through countless dramatizations and reinterpretations. Among them, Spike Lee’s film “Summer of Sam” (1999) stands out for its raw portrayal of New York City unraveling under paranoia. Unlike traditional crime films, Lee’s work isn’t about the killer — it’s about the city itself, the heat, the fear, and the madness. It paints a portrait of working-class neighborhoods trapped between disco lights and the echo of gunshots. The film humanized the terror ordinary New Yorkers endured, making the Son of Sam shootings 1976–1977 a living, breathing presence on screen.

More recently, Netflix’s “The Sons of Sam: A Descent Into Darkness” (2021) reopened the case with a fresh lens. The documentary explored journalist Maury Terry’s theory that Berkowitz hadn’t acted alone — that he was part of a satanic cult orchestrating the murders. While heavily debated, it reignited public interest and cast doubt on the simplicity of Berkowitz’s confession.

Whether or not these conspiracy theories hold truth, they reveal something deeper: society’s need to find meaning in senseless violence. The David Berkowitz crimes New York were so random, so motiveless, that the public struggled to accept them as the act of one man. This quest for explanation — spiritual, psychological, or conspiratorial — has kept his story alive for nearly five decades.

Culturally, the case also marked the dawn of true-crime media as we know it. From newspaper sensationalism to streaming documentaries, the Son of Sam saga became a template for how real crimes are packaged and consumed. It showed that society’s fascination with darkness can coexist uncomfortably with its demand for justice.

Today, David Berkowitz — now in his seventies — remains behind bars, still writing letters, still occasionally giving interviews about faith and forgiveness. But the world he once terrorized has never fully let go of the name Son of Sam. It stands as both a warning and a mirror — of how ordinary people, ordinary cities, and ordinary moments can suddenly fall apart under the weight of evil.

David Berkowitz’s Life in Prison: Transformation or Performance?

Since his conviction, David Berkowitz’s prison life has evolved into one of the most unusual narratives in modern criminal history. Initially, Berkowitz entered the system as a celebrity killer — reviled by the public, feared by inmates, and relentlessly examined by psychiatrists. Yet, over decades, he has carefully reconstructed his image from the “Son of Sam” to the “Son of Hope,” a transformation that continues to polarize psychologists, theologians, and the media.

When Berkowitz first arrived at Attica Correctional Facility in 1978, he was a target. Other inmates despised him for the panic he caused, and he was assaulted several times — once so violently that his throat was slashed, leaving a deep scar that nearly ended his life. After recovering, he was transferred to Sullivan Correctional Facility, and later to Shawangunk Correctional Facility in Wallkill, New York, where he remains incarcerated.

In his early years, prison guards described him as withdrawn, volatile, and prone to emotional breakdowns. He alternated between claiming to hear demonic voices and showing flashes of lucidity. Psychiatric evaluations revealed traits consistent with antisocial personality disorder, narcissism, and schizoid tendencies — classic components of the David Berkowitz psychology profile that criminologists still study today.

But in 1987, something shifted. Berkowitz claimed to have found God after receiving a Bible from a fellow inmate. He began attending chapel sessions, reading Scripture daily, and eventually renounced his old identity as the Son of Sam. In a letter to the press, he wrote:

“Jesus Christ has forgiven me and given me peace. He has taken away the evil that once consumed me.”

This born-again transformation gave birth to the persona he now calls the “Son of Hope.” Berkowitz began writing essays and letters to youth ministries, warning about the dangers of violence, Satanism, and fame. He published reflections online through Christian prison outreach programs, framing himself as a cautionary tale rather than a villain.

However, many question the sincerity of his transformation. Criminal psychologists argue that Berkowitz’s shift to religiosity could stem from narcissistic redemption seeking — a subconscious attempt to maintain relevance under a new, more socially acceptable identity. The same need for recognition that fueled his crimes might now drive his religious outreach.

Despite this skepticism, there’s no denying that Berkowitz’s demeanor has changed. Prison staff describe him as calm, cooperative, and deeply engaged in chaplaincy work. He mentors inmates, helps with literacy programs, and avoids the media unless the request aligns with his faith. His David Berkowitz prison life has been marked by multiple parole hearings — all denied, most recently in 2022. At every hearing, he insists he deserves to remain imprisoned, stating:

“I believe justice was served. I’ve done terrible things, and I don’t deserve freedom.”

Such admissions have softened public perception slightly, but not enough to erase the horrors of the Son of Sam shootings 1976–1977. For many victims’ families, Berkowitz’s conversion is a personal coping mechanism — not redemption. For others, it’s proof that even in darkness, some degree of moral awareness can surface.

His letters, now archived by criminologists and journalists, reveal a man who has come to understand the full weight of his crimes. He frequently writes about guilt, forgiveness, and the damage caused by fame-hungry violence. Yet, even in contrition, he remains a public figure — an unavoidable paradox.

Ultimately, David Berkowitz’s prison life raises one haunting question: can a man who embodied evil ever truly change? And if he does, does society owe him forgiveness — or eternal silence?

The Psychological Legacy: Understanding the Mind of the “Son of Sam”

Even decades later, David Berkowitz’s psychology profile continues to fascinate scholars in criminology and forensic psychiatry. His case sits at the intersection of individual pathology, media influence, and urban chaos — a perfect storm that turned ordinary fear into mass hysteria.

Modern criminologists classify Berkowitz as a mission-oriented serial killer — one who believed his murders served a higher, often delusional, purpose. His confessions about demons and commands from “Father Sam” fit a psychotic narrative, yet his strategic planning and awareness of police activity suggested control and calculation. This duality — rational planning blended with psychotic delusion — remains central to his psychological study.

Early evaluations diagnosed him with paranoid schizophrenia, but later assessments leaned toward psychopathy with delusional ideation rather than genuine psychosis. He wasn’t “mad” in the legal sense — he was aware his actions were wrong but justified them through his fantasies. His compulsive writing of Son of Sam letters to police and obsession with recognition demonstrated high-functioning intellect coupled with moral disintegration.

Researchers studying Berkowitz often reference the “social isolation hypothesis.” Raised in relative comfort but emotionally detached, he developed an internal world filled with resentment, inferiority, and distorted spirituality. His time in the military exposed him to weapons and discipline, but upon returning home, he fell into profound loneliness. The “voice” he claimed to hear may have been a manifestation of his subconscious need for purpose and power.

Furthermore, Berkowitz’s choice of victims — young couples and women — reflected a mix of envy, rejection, and unresolved maternal anger. His fixation on women mirrored an emotional wound that never healed. The David Berkowitz victims list represents, in essence, the tragic externalization of his internal torment.

Psychologists also examine how the media validation loop shaped his psyche. Every headline amplified his delusions, creating a feedback system of power. When he saw “Son of Sam” printed across front pages, it validated his alternate identity, solidifying his sense of divine mission. In this way, the David Berkowitz Son of Sam phenomenon became a case study in how fame can feed psychosis.

Today, his profile is a cornerstone of criminal psychology textbooks. It serves as a warning about how personality disorders, social neglect, and media glorification can intersect catastrophically. Forensic students analyze his interviews to distinguish genuine remorse from manipulative empathy — a lesson in detecting authenticity behind criminal repentance.

What makes Berkowitz’s psychology especially instructive is that it captures the evolution of modern serial killer archetypes. From delusional loner to media-savvy manipulator to repentant recluse — his trajectory mirrors society’s fascination with evil and redemption.

The David Berkowitz psychology profile, therefore, is not just the study of one man — it’s the study of how collective fear, moral panic, and individual pathology can spiral into an unforgettable chapter of human behavior.

Conclusion: The Shadow That Never Left New York

Nearly fifty years later, the story of David Berkowitz, the “Son of Sam,” still hangs over New York like a ghost. The Son of Sam shootings (1976–1977) were not merely a series of murders — they were a mirror to a city unraveling under fear, and to a society learning how powerfully violence could travel through media, myth, and memory.

His crimes redefined the landscape of criminal justice and journalism. The Son of Sam law New York established a moral boundary against exploitation; the NYPD’s handling of the case pioneered modern profiling; and the city’s residents learned firsthand how hysteria can spread faster than truth.

Through it all, Berkowitz remains a haunting contradiction — both a cautionary tale and an enigma. In prison, he preaches peace, yet his name still evokes terror. He calls himself the “Son of Hope,” yet the world will always remember the “Son of Sam.”

The David Berkowitz Son of Sam case forced America to confront uncomfortable truths about evil: that it can look ordinary, that it feeds on attention, and that it never truly disappears. From Spike Lee’s “Summer of Sam” (1999) to Netflix’s “The Sons of Sam: A Descent Into Darkness” (2021), his story continues to echo through culture — a testament to how tragedy becomes legend when retold through generations.

For victims’ families, the legacy is not cinematic or psychological — it’s personal and irreversible. For the public, it’s a grim reminder that fame and violence, when intertwined, can distort the very notion of justice.

As of 2025, David Berkowitz is still alive, still writing, still imprisoned — a man whose name will forever be synonymous with fear. The Son of Sam may have stopped shooting, but his shadow lingers in every true-crime story that seeks to understand why ordinary humans sometimes do extraordinary evil.

And in that sense, New York will always remember the summer when its streets fell silent — not from peace, but from the terror of one man’s madness.

Want to read a bit more? Find some more of my writings here-

Chia Seeds: The Tiny Powerhouse of Nutrition That Transforms Your Health

Book Review: As Good As Dead by Holly Jackson

When Tears Say What Words Can’t: A Poem About Crying Without Explanation

I hope you liked the content.

To share your views, you can simply send me an email.

Thank you for being keen readers to a small-time writer.