Few names in the annals of American crime evoke as much horror and fascination as Ted Bundy, the infamous serial killer whose charm, intelligence, and calculated brutality shattered the illusion that evil is always visible. Decades after his death, Bundy remains a grim study in the duality of human nature — a man who could be a law student one day and a murderer the next.

The Making of a Monster: Ted Bundy’s Childhood and Early Life

Ted Bundy’s story begins in Burlington, Vermont, on November 24, 1946. Born Theodore Robert Cowell, he was raised in an environment shrouded in deceit. His mother, Eleanor Louise Cowell, was unwed at the time of his birth — a scandal in 1940s America. To avoid social stigma, Ted’s grandparents claimed him as their own child, while his mother was introduced as his sister.

This complex lie formed the foundation of Bundy’s psychological profile — early exposure to secrecy, shame, and emotional dissonance that would later manifest in chilling ways. By the time he discovered the truth about his parentage, Bundy had already developed a deep-seated mistrust toward authority and an obsession with control.

Bundy was bright, articulate, and socially adept. He attended the University of Washington, where he studied psychology — a cruel irony that he would later use his understanding of human behavior to manipulate and destroy lives. In his youth, Bundy appeared ambitious, polite, even likable. Friends and professors described him as “intelligent and driven,” yet behind that polished façade, darkness brewed.

During his college years, Bundy began showing early signs of deviance: voyeurism, theft, and compulsive lying. He harbored resentment toward women who rejected him, particularly those resembling an early girlfriend who broke his heart — a woman of refined beauty and dark hair parted down the middle, a detail hauntingly reflected in many of his later victims.

The Psychological Mask: Ted Bundy’s Dual Identity

To understand Ted Bundy, one must delve into the psychology of serial killers. Bundy was not a disheveled loner or deranged outcast; he was an articulate, handsome man with ambitions of becoming a politician. His demeanor was so normal that people around him couldn’t reconcile it with the brutality he unleashed.

Psychologists later classified Bundy as a sociopath — someone incapable of empathy, guilt, or remorse. Yet, Bundy’s intelligence allowed him to mask these traits effectively. His charisma wasn’t an act; it was a weapon. He studied his victims’ vulnerabilities, mirrored their emotions, and gained their trust effortlessly.

This chilling duplicity made Bundy one of the most terrifying predators of the 1970s, an era when America was grappling with a new understanding of what a serial killer even was. Before Bundy, the concept of someone murdering repeatedly across states without clear motive was unthinkable. His calculated pattern and ability to evade law enforcement for years exposed massive flaws in inter-state policing systems.

The Murders That Stunned America

Between 1974 and 1978, Ted Bundy embarked on a cross-country killing spree that claimed the lives of at least 30 young women, though many experts believe the real number could be far higher. These crimes, known collectively as the Ted Bundy murders of the 1970s, began in Washington and Oregon before spreading to Utah, Colorado, and finally Florida.

Bundy’s victim-luring methods were as notorious as his crimes. Pretending to be injured — with his arm in a sling or leg in a cast — he would ask young women for help loading something into his car. His victims, often kind-hearted and unsuspecting, would assist him, only to be bludgeoned, abducted, and murdered.

His victims list included college students, sorority members, and even a 12-year-old girl named Kimberly Leach, whose murder ultimately sealed his fate. Bundy’s killings were methodical yet impulsive, organized yet driven by uncontrollable compulsion — a paradox that fascinated criminologists for decades.

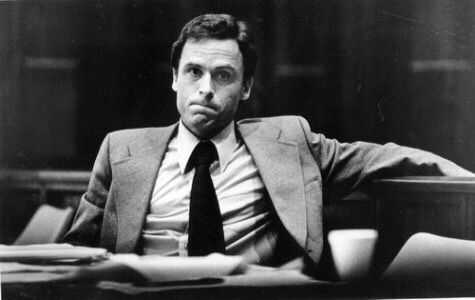

The Ted Bundy Trial: Charisma in the Courtroom

When Bundy was finally caught in 1978 after a series of escapes and arrests, America was glued to their televisions. The Ted Bundy trial highlights were unlike anything the nation had ever seen. For the first time, a serial killer represented himself in court, cross-examining witnesses, charming reporters, and manipulating the media with his intellect and confidence.

In a shocking twist, Bundy proposed to his long-time girlfriend Carole Ann Boone during his trial — exploiting a legal loophole that allowed a declaration of marriage in court to be recognized in Florida. The courtroom audience was transfixed; he had turned his murder trial into a grotesque performance of charisma and control.

Despite his theatrics, the evidence was overwhelming. Bundy was convicted of multiple murders, including the horrific Chi Omega sorority killings at Florida State University, and sentenced to death.

The Confession Tapes: A Glimpse Into the Mind of Evil

In his final years on death row, Bundy began to open up — albeit strategically. The Ted Bundy confession tapes, recorded in the late 1980s, revealed a chilling self-awareness. Speaking in the third person to distance himself from guilt, Bundy described his compulsions, techniques, and motivations with unnerving calmness.

He admitted to using pornography as a catalyst for his escalating violence, framing himself as both victim and perpetrator. Yet his statements were riddled with manipulation, revealing as much about his need for control as about the crimes themselves. These recordings later became the basis for documentaries such as The Ted Bundy Netflix documentary, which reintroduced his story to a new generation.

The Final Chapter: Ted Bundy’s Execution

After over a decade on death row, Ted Bundy’s execution date was set for January 24, 1989. Crowds gathered outside Florida State Prison, some chanting “Burn, Bundy, burn,” as news outlets broadcast live updates. At 7:16 a.m., Bundy was executed in the electric chair.

Even in his final moments, Bundy tried to maintain control — offering vague confessions and apologies that seemed designed to maintain mystery rather than closure. His death marked the end of a two-decade-long nightmare, yet the fascination with his psychology, methods, and persona endures.

Legacy and Influence: From Copycats to Pop Culture

Bundy’s crimes spawned copycat killers and inspired both fear and media fascination. The Christopher Wilder “Beauty Queen Killer” (1982–1984) modeled his victim-luring techniques on Bundy’s charm and deception. Danny Rolling, the Gainesville Ripper (1990), cited Bundy as a direct influence in his Florida student murders.

Hollywood too was captivated — Mark Harmon portrayed Bundy in The Deliberate Stranger (1986), shaping his media image as the “handsome killer.” Decades later, Zac Efron revisited the role in Extremely Wicked, Shockingly Evil and Vile (2019), reviving public discourse on how charisma and horror coexist.

Even Florida saw copycat crimes in the early to mid-1980s where kidnappers mimicked Bundy’s “injured arm” ruse — proof that his legacy transcended mere crime and entered the realm of myth.

Why Ted Bundy Still Matters

The story of Ted Bundy, serial killer, remains one of psychology’s most chilling case studies. He forces us to confront the uncomfortable truth that evil can wear a smile, shake your hand, and even ask for help.

For criminologists, Bundy’s case is a window into manipulation and the failure of early law enforcement systems. For psychologists, it’s a deep dive into narcissistic psychopathy. And for the public, it remains a haunting reminder that monsters don’t always hide in shadows — sometimes, they look like the boy next door.

FAQs

Who was Ted Bundy?

Ted Bundy was an American serial killer active during the 1970s, known for murdering numerous young women across several U.S. states.

How many victims did Ted Bundy kill?

Bundy confessed to killing over 30 victims, though experts believe the real number may be much higher.

How was Ted Bundy caught?

He was arrested multiple times for suspicious activity and ultimately caught in Florida in 1978 after a traffic stop uncovered stolen items linking him to previous crimes.

What methods did Ted Bundy use to lure his victims?

Bundy often feigned injury, pretending to have a broken arm or leg, and asked for help before abducting his victims.

When was Ted Bundy executed?

Ted Bundy was executed on January 24, 1989, in Florida’s electric chair.

Did Ted Bundy confess before his death?

Yes. In his final days, Bundy confessed to several murders in what became known as the “Ted Bundy confession tapes.”

What happened during Ted Bundy’s trial?

His trial was the first nationally televised serial murder case in the U.S., where Bundy represented himself, marrying his girlfriend mid-proceeding and using charm as a defense.

Was Ted Bundy married or in a relationship?

He was romantically involved with several women and legally married Carole Ann Boone during his trial, with whom he fathered a child.

Why is Ted Bundy still studied today?

Bundy’s case remains central in criminal psychology for understanding psychopathy, manipulation, and the societal allure of charismatic killers.

Ted Bundy: The Victims, The Media, and The Myth That Endures

While history often remembers Ted Bundy, the serial killer, as an enigma of charisma and cruelty, the true heart of this tragedy lies with his victims — bright, kind, promising young women whose lives were cut short by a man who weaponized charm itself.

Behind the psychological intrigue and media fascination lies a far more painful truth: Bundy’s story is not merely about the killer, but about the countless dreams he destroyed in the process.

The Women He Silenced: Remembering Ted Bundy’s Victims List

Between 1974 and 1978, Bundy’s violence stretched across the Pacific Northwest, the Rocky Mountains, and down into the southern U.S. His victims list reads like a roll call of lost potential — college students, daughters, sisters, each with her own story.

Confirmed victims include:

- Lynda Ann Healy (21) – Disappeared from her University of Washington dorm room in February 1974.

- Donna Gail Manson (19) – Vanished en route to a concert at Evergreen State College a month later.

- Susan Rancourt (18) – Last seen on her way to a dorm advisors’ meeting.

- Georgann Hawkins (18) – Abducted while walking between fraternity houses at the University of Washington.

- Janice Ott (23) and Denise Naslund (19) – Both vanished from Lake Sammamish State Park on the same July afternoon in 1974.

The pattern was horrifyingly consistent — young women with long brown hair, parted in the middle, often last seen helping a man with an arm sling or crutches. This modus operandi later became one of Bundy’s signature tactics.

By the time Bundy reached Utah, his confidence had grown into recklessness. He abducted and murdered multiple women while studying law, continuing to maintain a veneer of normalcy among peers and professors.

His final known victim, 12-year-old Kimberly Leach, was abducted from her junior high school in Lake City, Florida, in 1978. Her tragic death would become the keystone of Bundy’s conviction — and the reminder that no one, not even a child, was safe from his predation.

These are only the confirmed names. Many others — hitchhikers, runaways, or unidentified women — remain suspected victims of Bundy, whose true body count will likely never be known.

The Hunt for a Ghost: How Ted Bundy Eluded Law Enforcement

In the 1970s, before digital databases and nationwide forensic coordination, America was unprepared for a predator like Bundy. His crimes spanned multiple states — Washington, Oregon, Idaho, Utah, Colorado, and Florida — each with its own law enforcement jurisdiction and limited communication systems.

Investigators initially had no idea they were chasing the same man. Witnesses described a charming, polite stranger named “Ted” driving a Volkswagen Beetle, but the absence of DNA technology meant evidence was mostly circumstantial.

Bundy’s intelligence allowed him to stay several steps ahead. He changed appearances, license plates, and tactics frequently. He even volunteered on political campaigns and appeared in law enforcement volunteer projects, gaining insider access to investigative processes.

At one point, Bundy was actually placed on a list of suspects by Washington investigators but was dismissed — he seemed too intelligent, too normal, too… good. That underestimation was his greatest shield.

His eventual capture was a stroke of luck: in 1975, a Utah police officer pulled him over for a traffic violation and found burglary tools and suspicious items in his car. Even then, it took years — and multiple escapes — before Bundy’s crimes were fully connected.

When he was finally apprehended in Florida in 1978, fingerprints, bite marks, and eyewitness testimonies tied him directly to the Chi Omega sorority murders at Florida State University.

Bundy’s capture marked the beginning of a new era in American criminology — one that emphasized inter-agency coordination and behavioral profiling.

Ted Bundy and the Media: The Birth of a True Crime Obsession

The Ted Bundy trial highlights of 1979 turned a courtroom into a spectacle and a killer into a celebrity. America had never witnessed a trial like it — a handsome, articulate man defending himself against charges of unimaginable brutality.

The press couldn’t look away. Bundy’s smirks, his confidence, his sharp suits — they were front-page news. Women wrote him fan letters. TV networks broadcast daily updates. He wasn’t just a criminal; he became a dark cultural phenomenon.

Psychologists and media critics later reflected on this disturbing fascination. Bundy’s case blurred the line between horror and glamour, introducing a dangerous allure to criminal psychology that still lingers today.

The phenomenon resurfaced decades later with the Ted Bundy Netflix documentary and films like Extremely Wicked, Shockingly Evil and Vile starring Zac Efron. While these works aimed to depict his duality, they also reignited debates about how society sensationalizes serial killers.

Bundy knew how to perform — and the media, captivated by his intelligence, became his unwitting stage.

The Psychology of Control: Inside Ted Bundy’s Mind

To psychiatrists, Bundy was not merely a murderer but a case study in manipulation. His psychological profile fits the definition of a high-functioning psychopath: narcissistic, charming, emotionally cold, and devoid of empathy.

Bundy’s childhood and early life traumas — the lies about his parentage, his unstable identity, his feelings of rejection — may have fueled a lifelong rage disguised as confidence. Yet, unlike many killers driven by compulsion alone, Bundy’s crimes were meticulously calculated.

He derived pleasure not just from killing but from control — over his victims, over investigators, even over public perception. His behavior during trials and interviews was not random but strategic. He thrived on attention, bending narratives to his advantage.

Experts have noted that Bundy’s intelligence amplified his cruelty. He could analyze his impulses with chilling detachment, almost as if he were studying himself. In the Ted Bundy confession tapes, he described his acts as if recounting an experiment — devoid of emotion, full of precision.

This self-awareness — the ability to know evil intimately and embrace it — is what makes Bundy’s psychology so terrifying even today.

Echoes Through Time: Copycats and Cultural Reverberations

Ted Bundy’s crimes didn’t die with him. They echoed into the decades that followed, shaping both criminal behavior and media representation.

- Christopher Wilder (1982–1984), known as “The Beauty Queen Killer,” modeled his luring techniques — feigned injury, offers of help — directly on Bundy’s charm and deception.

- Danny Rolling (1990), “The Gainesville Ripper,” cited Bundy as an influence during his Florida student murders.

- Mark Harmon’s 1986 portrayal of Bundy in The Deliberate Stranger humanized the killer to an unsettling degree, creating a media archetype for the “handsome psychopath.”

- Zac Efron’s 2019 depiction in Extremely Wicked, Shockingly Evil and Vile reignited conversations about society’s fascination with charm and darkness.

- In the early to mid-1980s, several Florida copycat crimes mimicked Bundy’s “injured arm” ruse — proof that his manipulation techniques transcended his own actions.

These inspired incidents reflect Bundy’s enduring shadow — not admiration, but a chilling reminder of how manipulation and ego can breed imitation.

Why Ted Bundy Still Haunts Criminology Today

Even decades later, Bundy remains central to discussions in forensic psychology, law enforcement, and media ethics.

He exposed systemic flaws — from fragmented investigations to the ease with which charm can blind reason.

His case prompted the FBI to refine behavioral profiling methods, leading to the creation of the Behavioral Analysis Unit (BAU) — the same group dramatized in shows like Mindhunter and Criminal Minds.

Academically, Bundy’s profile is used to teach students about psychopathy, narcissism, and antisocial personality disorder. Emotionally, his case forces society to confront uncomfortable truths about our attraction to charisma and danger.

From the 1970s courtrooms to the Netflix documentaries, Bundy continues to fascinate because he represents a paradox: a man who could look into a camera, smile, and lie without hesitation — a reminder that true evil often hides behind intelligence, confidence, and charm.

A Legacy Written in Shadows

When Ted Bundy died in 1989, the world exhaled — yet the conversation didn’t end. His story reshaped the landscape of true crime, the nature of psychological study, and the portrayal of killers in popular culture.

Today, his name sits beside other infamous figures — not as a legend, but as a warning. The Ted Bundy murders of the 1970s remain a turning point in criminological history: a case that taught America that monsters don’t always come with fangs or masks; sometimes, they come with perfect smiles.

And perhaps that’s why Bundy still lingers in the collective memory — because he reminds us how fragile our instincts can be when evil looks ordinary.

Legacy of Terror: How Ted Bundy Transformed Criminal Profiling, Law Enforcement, and the Study of Evil

When Ted Bundy was executed in 1989, most Americans hoped to close the book on one of the most horrific chapters in modern crime. Yet, paradoxically, his death marked the beginning of something else — a new era of criminal investigation and behavioral science.

The Ted Bundy murders of the 1970s had forced law enforcement, psychologists, and journalists to confront an uncomfortable realization: serial killers could no longer be dismissed as deranged loners. They could be educated, persuasive, and socially embedded — like Bundy himself.

The Dawn of Criminal Profiling: Lessons from the Bundy Case

Before Bundy, serial killers were often treated as anomalies — unpredictable and incomprehensible. The FBI’s Behavioral Science Unit (BSU), formed in the early 1970s, was still developing frameworks for identifying recurring behavioral patterns. Bundy’s case became a real-world study that shaped how profiling evolved.

Agents like John Douglas and Robert Ressler, pioneers of what would later become the Behavioral Analysis Unit (BAU), studied Bundy’s methods meticulously. They realized that while his killings were impulsive in execution, they followed a consistent psychological pattern:

- Pre-crime fantasy: Bundy meticulously planned his abductions, often visiting crime scenes beforehand.

- Victim typology: His victims resembled one another — young, white, brunette, intelligent women — symbolizing his unresolved personal trauma.

- Control and dominance: He relished psychological superiority more than the act of killing itself.

This psychological mapping — linking motive, fantasy, and behavior — became the foundation of modern criminal profiling. The phrase “organized offender” was practically defined through Bundy’s behavioral patterns: intelligent, manipulative, socially functional, and methodical.

Today, every major profiling textbook cites Bundy as a pivotal case study for understanding psychopathy and organized serial murder.

Forensics Revolution: The Power of Consistency and Evidence

The Bundy case also revolutionized forensic collaboration across states. In the 1970s, local police departments operated in silos; there was no national database to connect crimes by geography, victim type, or MO (modus operandi).

Bundy exploited that weakness masterfully. Moving from Washington to Utah, Colorado, and finally Florida, he committed murders that investigators initially believed were unrelated. Each jurisdiction worked in isolation, unaware that the same man was killing across the map.

His case prompted the creation of inter-state communication systems, and years later, the Violent Criminal Apprehension Program (ViCAP) — a centralized database connecting behavioral, forensic, and geographic data of violent offenders.

When Bundy was finally convicted, bite-mark evidence from the Chi Omega murders became crucial in proving his guilt — a landmark moment for forensic odontology. Although bite-mark forensics has since faced scrutiny, at the time it underscored the need for scientific rigor in linking killers to their crimes.

Bundy’s downfall, ironically, was enabled by his own arrogance. During one of his escapes from custody in Colorado, he stole a car, got pulled over for driving erratically, and was caught with stolen credit cards. The same man who once outwitted an entire nation was undone by a simple traffic violation — proof that even the most cunning criminals leave traces when they believe themselves untouchable.

The Media’s Role: Building a Monster

The Ted Bundy trial highlights did more than showcase a criminal; they reshaped the relationship between the media and the justice system.

Bundy’s trials were among the first to be televised nationally. Reporters flooded the courtroom, audiences tuned in daily, and suddenly America had a new archetype — the “handsome killer.”

Bundy understood the media’s power instinctively. He smiled for cameras, flirted with female reporters, and even used live interviews to plead his innocence. He turned horror into theatre.

This created a troubling paradox: the same public fascination that condemned him also amplified his notoriety. After his execution date was announced in 1989, news networks ran countdowns, interviews, and retrospectives. Vendors outside Florida State Prison sold T-shirts reading “Burn Bundy Burn.”

The Ted Bundy Netflix documentary and later dramatizations such as Extremely Wicked, Shockingly Evil and Vile reignited debates on how true crime stories walk a fine line between education and sensationalism. Should we remember Bundy for the lessons his crimes taught or fear the fascination his persona still inspires?

Inside the Mind: The Enduring Fascination with Bundy’s Psychology

Psychologists continue to dissect Ted Bundy’s psychology profile to this day. He embodied a rare combination of traits: high intelligence, narcissistic charm, manipulative skill, and total emotional detachment.

Bundy’s intellect allowed him to mimic humanity with precision. He studied empathy without ever feeling it — like an actor who memorizes compassion as a script. This imitation of normalcy is what makes psychopaths so dangerous; they can blend in effortlessly until it’s too late.

One of Bundy’s most chilling statements came during his death-row interviews:

“We serial killers are your sons, we are your husbands, we are everywhere. And there will be more of your children dead tomorrow.”

It was a haunting acknowledgment that he wasn’t an outlier — he was a mirror. His crimes forced society to recognize that evil doesn’t always wear an obvious mask.

Modern psychiatry uses Bundy’s case to illustrate psychopathy vs. sociopathy — two related but distinct disorders. While sociopaths are volatile and emotionally erratic, psychopaths like Bundy are calculated and cold. His control, charm, and intelligence made him the model profile for a “clinical psychopath.”

The Academic Legacy: Bundy in Modern Education and Forensic Studies

Today, Ted Bundy occupies entire sections in criminology textbooks and psychology syllabi. His childhood and early life, his manipulative behavior, and his crimes serve as a cornerstone in studying deviant psychology.

Students dissect his confession tapes to understand denial, rationalization, and linguistic self-distancing — techniques still observed in modern offenders. Bundy’s manipulation of both victims and media remains a prime example of narcissistic control dynamics.

Universities and FBI academies use Bundy’s timeline to train investigators on recognizing early behavioral signs of predation: compulsive lying, voyeurism, cruelty masked as confidence, and the escalation from fantasy to reality.

More importantly, his case influenced major systemic changes:

- Creation of inter-agency databases like ViCAP.

- Expansion of forensic psychology as a legitimate academic discipline.

- Implementation of victimology — the study of victim traits and risk factors — to prevent similar crimes.

The Moral Reflection: Why Bundy Still Matters

Why, decades later, do we still study Ted Bundy, the serial killer? Why does his story appear in documentaries, criminology lectures, and cultural discussions?

Because Bundy is not just history — he’s a psychological mirror. He exposes humanity’s vulnerabilities: our instinct to trust charm, our fascination with danger, and our inability to believe that evil can look ordinary.

His story teaches caution but also awareness. It pushed law enforcement to evolve, inspired generations of psychologists to study psychopathy, and forced society to redefine what “normal” looks like.

In the 1970s, America believed monsters lived in the shadows. Bundy proved they could live in daylight — holding doors open, smiling politely, shaking hands.

And that revelation changed everything.

Closing Reflection

The world has moved on since that January morning in 1989 when Ted Bundy’s execution finally ended his reign of terror. Yet his presence lingers — in every textbook, every documentary, every cautionary tale about trusting appearances.

From the Ted Bundy murders of the 1970s to the Netflix documentaries of today, his name remains a cautionary legend. But perhaps the greatest tribute to his victims is not the fascination with Bundy himself, but the vigilance his story has inspired — a generation of investigators, psychologists, and citizens determined never to let charisma blind truth again.

Riya’s Blogs revisits his legacy not to glorify the killer, but to honor the victims, the lessons, and the progress born from tragedy. Bundy may have sought control through fear, but in the end, his crimes gave rise to a global determination to understand — and prevent — evil in human form.

Want to read a bit more? Find some more of my writings here-

The Shifting Room: A Short Story

The Ultimate Guide to Smoothie Recipes: Blending Nutrition, Flavor, and Joy

25 Quotes About Patience and Inner Calm

I hope you liked the content.

To share your views, you can simply send me an email.

Thank you for being keen readers to a small-time writer.