Written by: Akshika Jangid

India is the world’s most populous country in the world as there has been an increase of .92% (more than a crore every year). This increasing population puts a pressure on scarce resources and services that leads to unemployment, environmental degradation, social and climate injustice. While we want the maximum good per person but the question that arises to my mind is that; Is this practically possible ? This Population Problem has made many of us concerned about the scarcity of resources we share and the competition over these common resources that our future generation will eventually face. Economists call this problem ‘The Tragedy of the Commons’ which applies to shared spaces, natural resources and information.

Population, as the famous sociologist Thomas Malthus has defined, tends to increase geometrically or what the economists say, exponentially. This means that in a finite world, the per capita of the world’s resources must steadily decrease. We live in an infinite world with endless demands and desire to create more but this creates a tension with the ecological limits of our planet. Malthus’s theory, which states that while population tends to increase geometrically (exponentially), the resources—most notably food—tend to increase only arithmetically (linearly). In a finite world, this mismatch, according to him, inevitably leads to decreasing per capita resources over time, resulting in cycles of scarcity, poverty, and checks on population growth such as famines and diseases.

Despite being deeply influenced by utilitarian philosophy, especially Jeremy Bentham’s principle, Hardin believed societies that continue to grow without check will require ever-greater sacrifices, making Bentham’s vision of “the greatest good for the greatest number” even more difficult to achieve. In today’s world, Hardin observes, the countries experiencing the fastest population growth are often the ones least equipped in terms of resources.

It is practically impossible that maximizing population can maximize goods but as Gardin says, in reality if we really want to reach an optimum population size then we will have to explicitly get rid of the spirit of Adam Smith’s idea of ‘Invincible Hand’ in the field of practical demography.

Hardin’s Utilitarian Worldview

For Hardin, collective welfare sometimes demands individual sacrifice—personal freedom could not automatically take precedence over communal sustainability. He was, predictably, a controversial figure; his positions on issues like immigration, abortion, and population control often provoked sharp criticism, including allegations of elitism, racism, and insensitivity to the disadvantaged.

Yet, despite his polemical tone and problematic views on topics such as racial intelligence and poverty, Hardin’s pragmatic outlook and focus on scientific reasoning have ensured his continued influence in debates about shared resources and collective ethics.

Garrett Hardin’s “Tragedy of the Commons”

I refer to the famous essay titled, “The Tragedy of the Commons,” famously published in 1968, as rebuttal to the role of invincible hand in population control. Hardin—a polymath who simultaneously wore the hats of economist, ecologist, and microbiologist—crafted a compelling narrative that remains powerfully relevant as humanity grapples with degradation of natural resources, staggering population growth, and moral dilemmas surrounding privatization, public good, and the use (and misuse) of common property.

While Hardin does acknowledge the usefulness of the idea of ‘Invincible Hand’ in many economic contexts, he also warns of its dangers when applied to the sphere of reproduction and resource use. Garrett’s Tragedy of Common is a direct critique to this Idea that individual actions in self interests will automatically lead to best possible outcomes for everyone.

Hardin argues that individuals acting in their own self interests with shared resources does not always result in the best outcome for the community, as it would often result in depletion or overexploitation.

For example; The demand of copper nowadays has increased primarily because of its cooling properties but its requirement for different people would also vary, such as a blacksmith would use it to increase its production of more copper vessels while a technician who works at an AI Centre would also want to make the best use of copper so as to consume less power.

Thus, maximizing population would not maximize goods for all; rather, without collective management or ethics that transcend individualism, the commons (resources and the environment) suffer.

In his view, many of the most pressing environmental and social challenges cannot be solved by technical solutions alone, but require fundamental changes in human values and ethics.

Warnings Against “Technical Solutions”

In introducing “The Tragedy of the Commons,” Hardin warns that “technical solutions” to social and ecological problems can sometimes worsen the very issues they are supposed to address. He uses the Cold War nuclear arms race as a metaphor: each new technological advancements—intended to ensure security—actually heightened global danger, ultimately making the world more fragile, not less.

Hardin suggests that actual solutions to large-scale problems lie not in new technologies but in advances in collective ethics and social organization. As technology empowers societies to grow larger and more complex, the burdens they place on the environment deepens further. Without parallel growth in moral restraint, the destructive potential of a rapidly multiplying human population becomes uncontainable.

Tragedy of Freedom in the common: Individual Interest and Collective Ruin

If freedom of action—especially the freedom to reproduce—is left unregulated, it leads to an ever-increasing population and escalating strain on the world’s natural systems. As Hardin puts it, “the freedom to reproduce may have to be restricted,” because individual choices, when aggregated, can erode the foundation of common prosperity.

Hence, Individual freedom in reproduction when left unchecked, it becomes a threat to the very commons on which “WE” all depend.

Freedom in the commons brings ruin to all….

To quote Hardin, “Ruin is the destination toward which all men rush, each pursuing his own best self interest in a society that believes in the freedom of the commons.”

Hardin explains this argument with the help of an example of the herders sharing a communal pasture. Each herder stands to benefit by adding additional livestock, grazing more animals than the land can sustainably support, because each additional animal brings private gain. However, the resulting overgrazing depletes the field—a loss shared by all. The “tragedy” is not in the inevitability of destruction, but in how rational, self-interested behavior by individuals leads, inexorably, to collective ruin.

This logic is still relevant to myriad modern examples even today ranging from overgrazing on federally owned rangelands, overfishing in the world’s oceans and overcrowding and ecosystem damage in national parks.

Whenever resources are held in common, overuse becomes likely, unless some external constraint—law, custom, or moral consensus—is imposed.

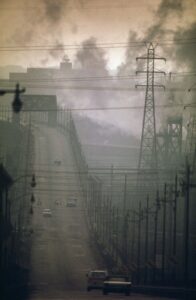

Pollution: The “Reverse Tragedy” of the Commons

Pollution, for Hardin, is another “tragedy of the commons.” Every polluter gains a private benefit by dumping waste into the public environment, while the community bears the cost in the form of ecological degradation. Over time, the accumulation of pollutants inexorably stresses the commons—clean rivers, air, soil—leading to declining quality of life for all.

A rational man finds his share of the cost of the wastes he discharges into the commons less than the cost of purifying his wastes. While this may be true for most of us, we are locked into a belief system of ‘Fouling our own nest’, so long as we behave as independent, national free-enterprisers.

Imagine a world where everyone fiercely guards their food baskets, making sure it stays fresh and untouchable because it is theirs but when it comes to the air we breathe, water we intake and use, why is the tragedy of the commons the most inevitable consequence?

Just because they belong to all, nobody feels responsible for it.

The owner of the factory on the riverbank sways away from taking the responsibility that the factory is the main reason for the polluted river, leaving the larger chaos for everyone else to deal with. Laws and fines try to patch this problem but they are just bandaids when everyone’s main goal is to protect themselves. It’s like being stuck in a game where cleaning after yourself isn’t rewarded, so everyone just passes the problem to someone else. In the end, unless we go beyond our narrow self interests and start thinking as a true community, the commons will always bear the cost. Moreover, the pollution problem inevitably becomes a consequence of larger population problem.

While banning plastic is easy, legislating temperance is no easy task. Tradition rules like “Thou shall not…” don’t work well for situations like pollution in crowded metropolitan cities. So, instead of enforcing strict laws, knowing that plastic use is everywhere in our lives, its better to have flexible rules managed by honest officials who can get feedback and can adjust as needed. The biggest challenge, however, is making sure these officials stay honest and rules stay fair. The morality of pollution is complex, often depending on seemingly minor contextual factors. In some cases, actions intended to curb ecological harm have unintended consequences—a recurring theme in Hardin’s analysis of legislative and moral reforms.

The Limits of Conscience: Why Voluntary Restraint Fails

Can appeals to conscience and goodwill, such as urging parents to have smaller families “for the good of humanity,” be effective in averting the tragedy?

Well, Hardin seems quite skeptical. He draws on Darwinian logic to suggest that voluntary restraint is insufficient: those who heed appeals for family planning have fewer descendants, while those who ignore them have more. Over generations, the restraint disappears, and unsustainable growth resumes.

This, for Hardin, is the “self-eliminating nature of conscience”—a compelling argument for how moral appeals alone cannot solve collective action problems. Instead, what is needed is what he calls “mutual coercion, mutually agreed upon”: a system of incentives and punishments, collaboratively created and imposed, to ensure sustainable behavior.

Mutual Coercion: The Case for Regulation

Hardin’s most controversial yet arguably most practical prescription is the necessity of restraint through mutual coercion. In other words, societies must agree—explicitly or implicitly—to impose rules that might be individually disliked, but are collectively essential. These can take the form of taxes, laws, regulations, fines, or other mechanisms that limit individual consumption, reproduction, or pollution, for the greater good.

As Hardin cautions, such coercion is not a license for authoritarianism but rather a recognition of necessity. In a crowded planet where almost all resources are under pressure, only purposely designed institutions—grounded in collective agreement—can protect shared goods from overuse and destruction.

This “recognition of necessity”—the acceptance of this tragedy that was once optional when population was sparse is now mandatory—forms the heart of Hardin’s plea. Without proper mechanisms for regulating access and use, modern societies risk not only impoverishing themselves, but also undermining the hopes of future generations. In Hardin’s own words, the symbolic wealth of the commons “has become a liability,” compelling us to rethink the ethics of freedom and responsibility in a finite world.

On the other hand, critics have argued that his emphasis on coercion sometimes gives little attention to the power of cultural norms, education, and democratic negotiation. For example, in many fishing communities, people have developed traditional rules about when and how much fish they can catch. These rules, agreed upon by the community, help prevent overfishing without needing strict government control. This shows that people can cooperate and manage commons well when they communicate and build trust.

Many have also claimed that his ideas only apply narrowly to ecological problems and not to complex social issues.

Lessons to learn today

Despite its limitations, “The Tragedy of the Commons” remains foundational. By recognizing the finite nature of Earth’s resources and the dynamics of incentives in shared systems, societies can build more effective—and equitable—institutions for managing common goods. Be it addressing the climate crisis, pollution, and population, Hardin’s insights are a call to balance freedom with the imperative of survival. The lesson of the commons is stark: only by nurturing a “recognition of necessity”, evolving communal ethics and educating ourselves, humanity can truly hope to avert tragedy and secure a sustainable future for themselves.